预算感知的工具使用实现有效的智能体规模化

Budget-Aware Tool-Use Enables Effective Agent Scaling

摘要

对大语言模型(LLM)进行测试时计算扩展,能在多类任务上提升性能,这一思路也被推广到工具增强智能体。对这类智能体而言,扩展不仅包括用更多 token 进行“思考”,也包括通过工具调用进行“行动”;工具调用次数直接限制了智能体与外部环境的交互上限。

然而,我们发现仅仅给智能体更大的工具调用预算并不会带来性能提升:由于缺乏“预算感知”,标准智能体很快会触及性能天花板。

为此,我们研究在显式工具调用预算约束下,如何有效地扩展此类智能体,并以网页搜索智能体为重点。我们首先提出 Budget Tracker:一种轻量级、可插拔的组件,持续向智能体提供预算状态,从而实现简单而有效的扩展。

我们进一步提出 BATS(Budget Aware Test-time Scaling):一个更完整的框架,在预算感知的基础上动态调整规划与验证策略,根据剩余资源决定是沿着有希望的线索“深挖”,还是“转向”新的路径。

为了在可控条件下分析成本–性能扩展,我们形式化了一个统一成本指标,同时计入 token 与工具消耗的经济成本。我们给出首个关于预算受限智能体的系统研究,表明预算感知方法能够产生更理想的扩展曲线,并推进成本–性能的帕累托前沿。

本工作为理解工具增强智能体的扩展规律提供了更透明、更有原则的实证视角。

1. 引言

对大语言模型(LLM)进行测试时计算扩展(test-time compute scaling)可以在包括推理、编码在内的广泛任务上提升性能[1,2,3,4]。主流的扩展策略如顺序扩展[5]与并行扩展[6,7],能够让模型投入更多努力、诱发更深层反思并迭代精炼输出,往往带来显著的答案质量提升[8]。这些成功经验也推动了将测试时扩展推广到工具增强智能体[9,10]:此时 LLM 被赋予搜索引擎、API 等多种工具,与外部环境交互。

对工具增强智能体的测试时扩展,同时扩大了“思考”(token)与“行动”(工具调用)。在纯文本推理任务中,扩展通常通过消耗更多 token 来实现;但对智能体而言,仅增加内部思考往往并不最优,也并不总能转化为性能提升[11]。不同于在文本推理中控制 token 数量[12,13],在网页浏览等智能体任务中,工具调用次数直接决定了探索的深度与广度[14,15],也就界定了可访问的外部信息边界。

然而,简单地给智能体更多测试时工具调用资源,并不能保证更好的性能。我们的分析揭示了一个关键瓶颈:标准智能体缺乏内生的预算感知。没有显式信号时,它们往往只进行浅层搜索[16],即使预算增加也无法有效利用额外资源。正如后续实证结果所示,标准智能体会快速触及“性能天花板”:无论额外预算多大,其能力都会趋于饱和。问题不在于花得更多,而在于如何花得更聪明——单次工具调用的边际收益并不确定,因此每一次调用都必须以策略性的方式使用。

这种独特的复杂性引出一个关键研究问题:在给定资源预算下,工具增强智能体如何才能有效地实现规模化(scaling),把预算用到最有价值的地方?我们在预算受限的设定中研究该问题,并以配备 Search 与 Browse 工具的搜索智能体为基础:这类智能体在实践中被广泛采用[17,18],且天然需要大量工具调用来收集外部信息。为确保比较公平与透明,我们形式化了一个统一成本指标,将内部 token 消耗与外部工具交互的经济成本合并计入,使我们能够描绘真实的成本–性能扩展趋势。

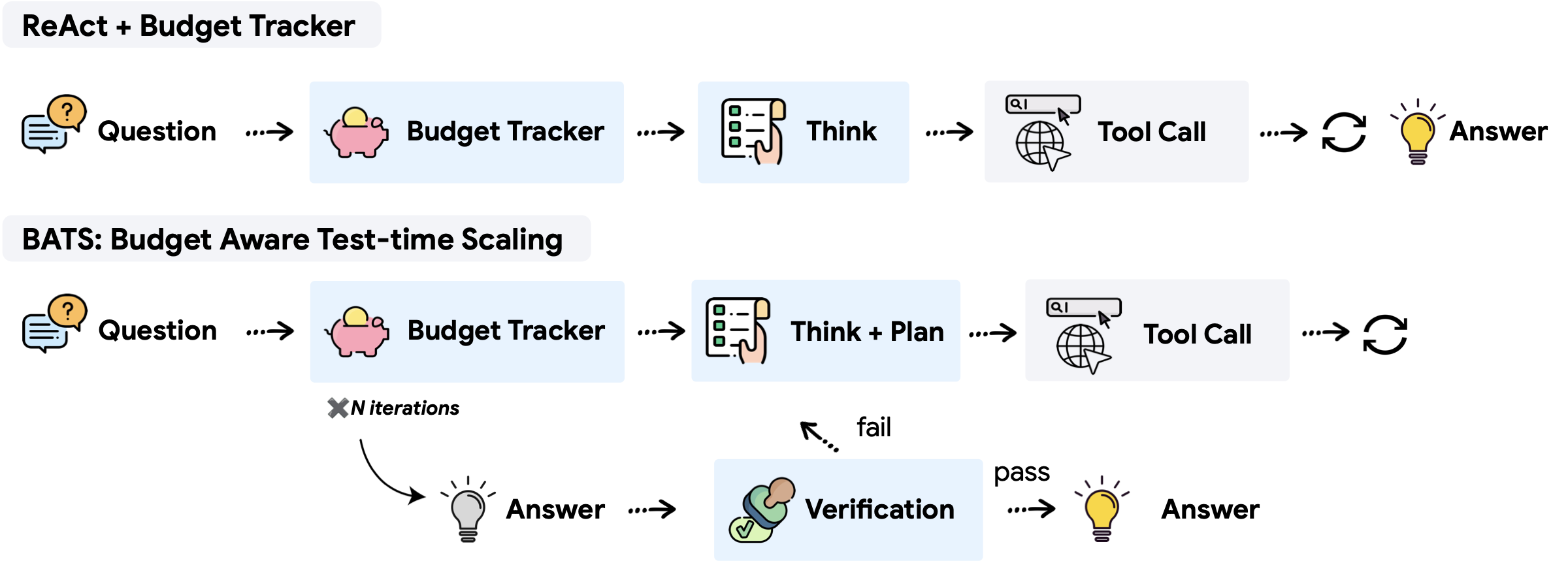

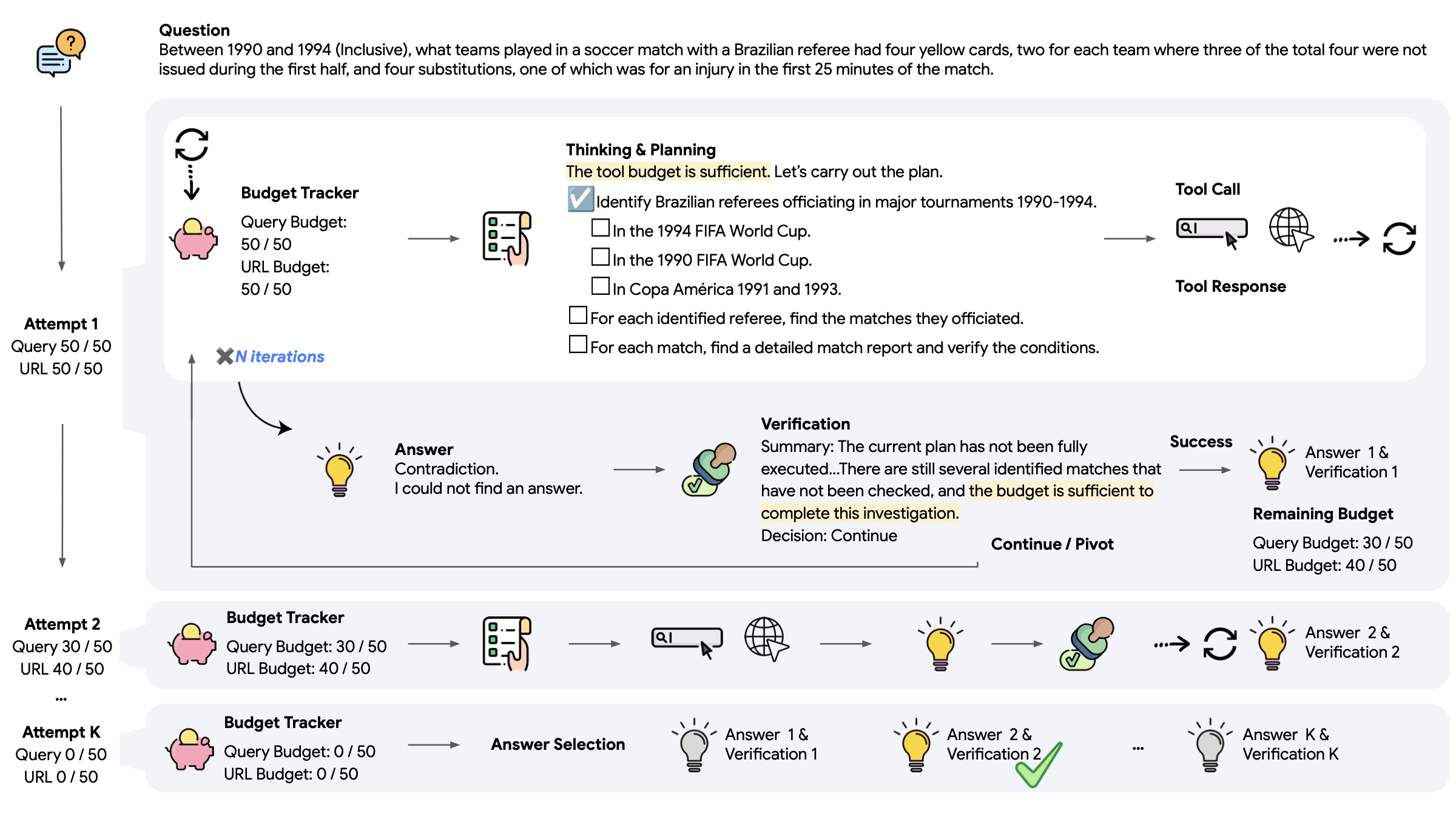

我们首先提出一种直观、轻量的方法:Budget Tracker(图 1 上),它是一个即插即用模块,可与大多数基于 ReAct 的智能体兼容[19]。Budget Tracker 持续向智能体提供资源可用性的连续信号,是一种简单但有效的方式,让智能体能够进行预算感知的工具使用。通过大量实验,我们表明这一插件能在多种预算约束下提升性能。将这种显式预算感知与传统测试时扩展策略结合,也能稳定地带来更有效的扩展行为,并持续推进成本–性能的帕累托前沿。

虽然仅提供“意识”已经有效,但它仍受限于智能体预先固定的逻辑。为进一步打破扩展天花板并让资源约束真正内化到决策中,我们提出 BATS(Budget Aware Test-time Scaling)(图 1 下):一个旨在在任意给定预算下最大化智能体性能的框架。BATS 的核心是维持对剩余资源的连续信号,并据此动态调整行为:规划模块根据当前预算调整每一步的投入;验证模块则结合资源状态决定是沿着有希望的线索继续“深挖”,还是在预算允许时“转向”其他路径。

我们的实证研究系统地评估了总资源成本与任务性能之间的关系:在不同预算下对比不同扩展框架。结果表明 BATS 产生更理想的扩展曲线:在更少工具调用、总体成本更低的情况下取得更高性能。以上发现说明预算感知设计能够显著提升工具增强智能体的有效性与效率,也凸显了在智能体测试时扩展中显式计入成本的重要性。

我们的贡献总结如下:

- 我们形式化了带显式工具调用预算的智能体测试时扩展,并提出统一成本指标,从而给出首个关于预算受限工具使用智能体的系统研究。

- 我们提出 Budget Tracker:一个轻量、可插拔模块,可与任意智能体编排框架兼容,从而实现有效的预算感知工具使用。

- 我们提出 BATS:一个预算感知框架,可基于实时资源追踪动态调整规划与验证策略,并在“深挖线索”与“分支转向”之间灵活切换。

- 我们在不同预算与统一成本度量下,基于搜索智能体进行了系统实验,证明 BATS 更具成本效益,能得到更理想的扩展曲线与更优的成本–性能权衡。

2. 问题表述

2.1 智能体测试时扩展

我们将智能体测试时扩展形式化为:智能体的性能如何随其对外部工具交互的预算而变化。这是对文献 [11] 中“测试时交互扩展”更一般概念的细化。为了让智能体测试时扩展更具成本效益,理想的智能体应当能在扩展曲线上任意预算约束下都达到尽可能高的性能。为此,我们的目标是设计一个有效且高效的智能体框架(策略)$\pi$:在严格的工具调用预算约束下最大化答案准确率。

设智能体配备 $K$ 个工具 $\mathcal{T} = \{t_1, \dots, t_K\}$。对给定问题 $x \in \mathcal{X}$,智能体在预算 $\mathbf{b}=(b_1,\dots,b_K)$ 下工作,其中 $b_i$ 表示工具 $t_i\in\mathcal{T}$ 的最大可调用次数。令 $\hat{y}_\pi(x)$ 表示策略 $\pi$ 对问题 $x$ 的预测答案,$y(x)$ 为其真实答案;令 $c_i(x;\pi)$ 表示在 $x$ 上实际调用工具 $t_i$ 的次数。我们将智能体测试时扩展表述为如下带预算约束的优化目标:

这里的目标是对所有问题的期望准确率。约束保证:对任意给定问题,每种工具的实际调用次数都不会超过其分配预算。通过在不同预算水平下评估智能体性能,我们可以描绘性能–成本曲线,从而刻画智能体的测试时扩展行为:它在多大程度上能将预算资源有效转化为问题求解能力。

预算 vs. 成本。我们区分预设的预算约束(规定工具调用的最大可用次数)与实现的成本(执行过程中实际消耗的资源)。预算提供硬上限,但最终成本取决于智能体策略。为便于更一致、更全面的比较,我们将在第 2.2 节引入一个后验的统一成本指标,用于分析智能体的测试时扩展。

预算选择。在多种可选约束中,我们优先采用“工具调用预算”而非“token 预算”,原因在于其相关性、一致性与可实践性。工具调用上限相比内部推理 token 更直接、更相关地限制了智能体获取外部知识的能力;这一选择也与既有实践保持一致[11,15]。此外,对复杂多步的智能体任务,预先确定合适的 token 预算往往并不容易;工具调用预算更便于设置与管理。尽管我们以工具调用定义预算,仍会在统一成本指标中纳入 token 使用(见第 2.2 节),以保证比较更公平、更透明。

2.2 搜索智能体实例化

在本文中,我们以搜索智能体作为测试时扩展问题的具体实例化:该设定具有广泛适用性,并拥有较成熟的基准体系。

搜索智能体是一个 LLM:它通过检索外部证据并在其上推理来回答信息查询问题 $x$。智能体遵循迭代式 ReAct 循环[19],在内部思考与外部行动之间交替。它可以访问两类主要工具与外部世界交互:

- Search。执行标准搜索引擎查询。给定文本查询,返回一组搜索结果(标题、摘要片段与 URL)。

- Browse。给定具体 URL,抓取对应网页的完整内容,提供通常在搜索摘要中不可见的细节信息。

统一成本指标。我们将智能体总成本建模为两类资源消耗之和:token 与工具调用。为形成统一度量,我们将两者映射到对应的经济成本:

- Token 成本。代表智能体内部认知努力,包括推理、规划与对参数化知识的处理。Token 成本按模型提供方的计费规则计算,并区分输入、输出与缓存命中(cache hit)token。在多轮迭代框架中,第 $i$ 次迭代的输出会成为第 $i+1$ 次迭代的输入的一部分;重叠部分会作为缓存命中,从而降低 token 成本。

- 工具调用成本。代表智能体通过信息查询动作与外部环境交互的开销。每次调用外部服务(例如一次搜索查询或一次浏览请求)都产生由对应 API/第三方提供方定价决定的成本。

对在策略 $\pi$ 下求解问题 $x$ 的一次执行,其统一成本 $C_{\textit{unified}}(x;\pi)$ 为 token 成本与工具成本之和。令 $c_i(x;\pi)$ 为工具 $t_i$ 的实际调用次数,$P_i$ 为每次调用的经济成本,则:

其中 $c_{\textit{token}}(x;\pi)$ 表示在问题 $x$ 上推理过程的 token 计费成本。该表述允许我们在不同预算约束 $\mathbf{b}$ 下,统一分析一次执行中真实发生的成本。两种成本维度并非独立:更多工具调用通常会增加 token 消耗,因为智能体需要处理与推理更多检索到的外部信息。

3. 预算感知

3.1 Budget Tracker

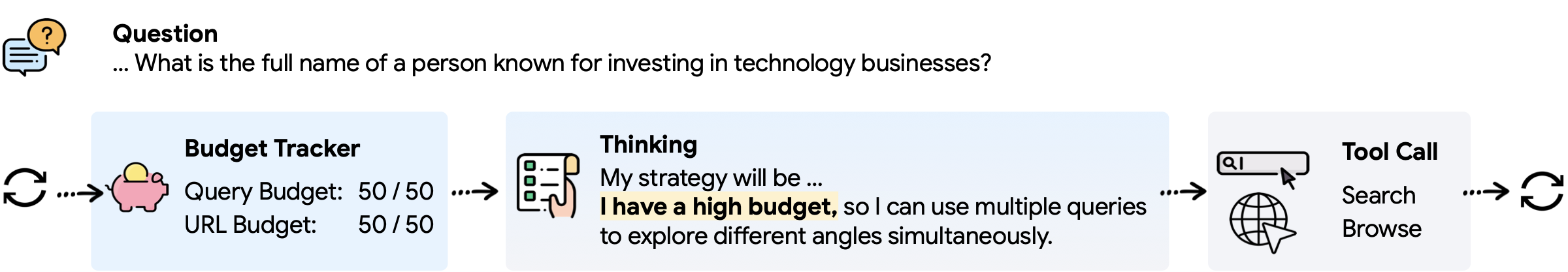

每次工具调用都会带来不可忽视的上下文与计算成本。我们的假设是:向模型提供显式预算信号,可以让它在无需额外训练的情况下内化资源约束,并据此调整策略。

我们提出 Budget Tracker:一个轻量、即插即用的模块,在智能体的推理循环中暴露实时预算状态。首次迭代时,Tracker 会提供一段简短的策略指南,描述不同预算区间及对应的工具使用建议(见附录 C)。此后每次迭代,Tracker 会附加一个预算状态块,展示每个可用工具的已用与剩余预算:

<budget>

Tool$_{1}$ Budget Used: ##, Tool$_{1}$ Budget Remaining: ##

Tool$_{2}$ Budget Used: ##, Tool$_{2}$ Budget Remaining: ##

Make the best use of the available resources.

</budget>尽管形式简单,Budget Tracker 完全在提示词层面工作,却能让智能体显式感知资源消耗与剩余预算,从而在后续推理中条件化地调整策略。

3.2 在预算感知下扩展

为更好理解不同预算约束下智能体行为的扩展方式,我们考察两种主流测试时扩展范式:顺序扩展与并行扩展。

在顺序扩展中,我们采用预算强制(budget-forcing)策略[3]:当智能体给出答案时,附加如下提示——“等等,你还有剩余的工具预算;在下结论前请使用更多 search 与 browse 工具探索不同信息来源。” 这会鼓励模型重新评估其推理并更充分利用可用工具调用。

在并行扩展中,我们固定单次运行的预算,并并行进行多次独立运行。我们按照常见测试时扩展实践[20] 报告 Majority Vote、Best-of-N 与 Pass@N;更多细节见附录 B.2。

3.3 结果与分析

我们在三个需要外部搜索的信息查询问答数据集上评估 Budget Tracker:BrowseComp[20]、BrowseComp-ZH[21] 与 HLE-Search[22,23]。数据集细节与完整实验设置见第 5 节。

在 ReAct 框架基础上,我们在每次工具响应之后立即插入 Budget Tracker,以告知智能体剩余预算。每个工具预算设置为 100;当任一预算耗尽或智能体到达最终答案时终止推理过程。

| 模型 | 方法 | BrowseComp | BrowseComp-ZH | HLE-Search |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini-2.5-Pro | ReAct | 12.6 | 31.5 | 20.5 |

| + Budget Tracker | 14.6 | 32.9 | 21.8 | |

| Gemini-2.5-Flash | ReAct | 9.7 | 26.5 | 14.7 |

| + Budget Tracker | 10.7 | 28.7 | 17.3 | |

| Claude-Sonnet-4 | ReAct | 12.2 | 29.1 | 20.5 |

| + Budget Tracker | 14.0 | 31.1 | 23.0 |

表 1:Budget Tracker 对工具使用行为与性能的影响:在不同模型与数据集上稳定提升答案准确率(结果为三次运行的平均)。

在相同预算下,Budget Tracker 能取得更高性能。表 1 在相同预算限制下对比了有无 Budget Tracker 的 ReAct。对不同模型,加入 Tracker 都能在所有数据集上提升准确率。这说明显式的预算信号能促使智能体更策略性、更积极地使用工具。

| 方法 | 预算 | Acc (%) | # search | # browse | 统一成本 (¢) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ReAct | 10 | 10.3 | 7.87 | 0.60 | 5.2 |

| 30 | 10.5 | 13.77 | 1.33 | 8.0 | |

| 100 | 12.6 | 14.24 | 1.36 | 9.9 | |

| ReAct + Budget Tracker | 10 | 12.8 | 8.48 | 1.09 | 6.8 |

表 2:使用 Gemini-2.5-Pro 时,不同预算下的性能与资源消耗对比。Budget Tracker 在预算减少 $10\times$(10 vs. 100)时仍能取得可比甚至更高的准确率,同时工具调用更少、总体成本更低,体现了显式预算感知的收益。

在相近准确率下,Budget Tracker 使用更少资源、成本更低。表 2 中“消耗资源”报告了平均 search 与 browse 调用次数,以及结合工具使用与 token 消耗的统一成本。对 ReAct 而言,提升预算能带来一定性能提升,但也会提高工具调用频率与总成本;相对地,Budget Tracker 在更少预算(10 vs. 100)下即可取得可比甚至更高准确率,并在该对比中将 search 调用减少 40.4%、browse 调用减少 21.4%、总体成本降低 31.3%。这表明显式预算感知能在不牺牲准确率的前提下提升工具使用效率。

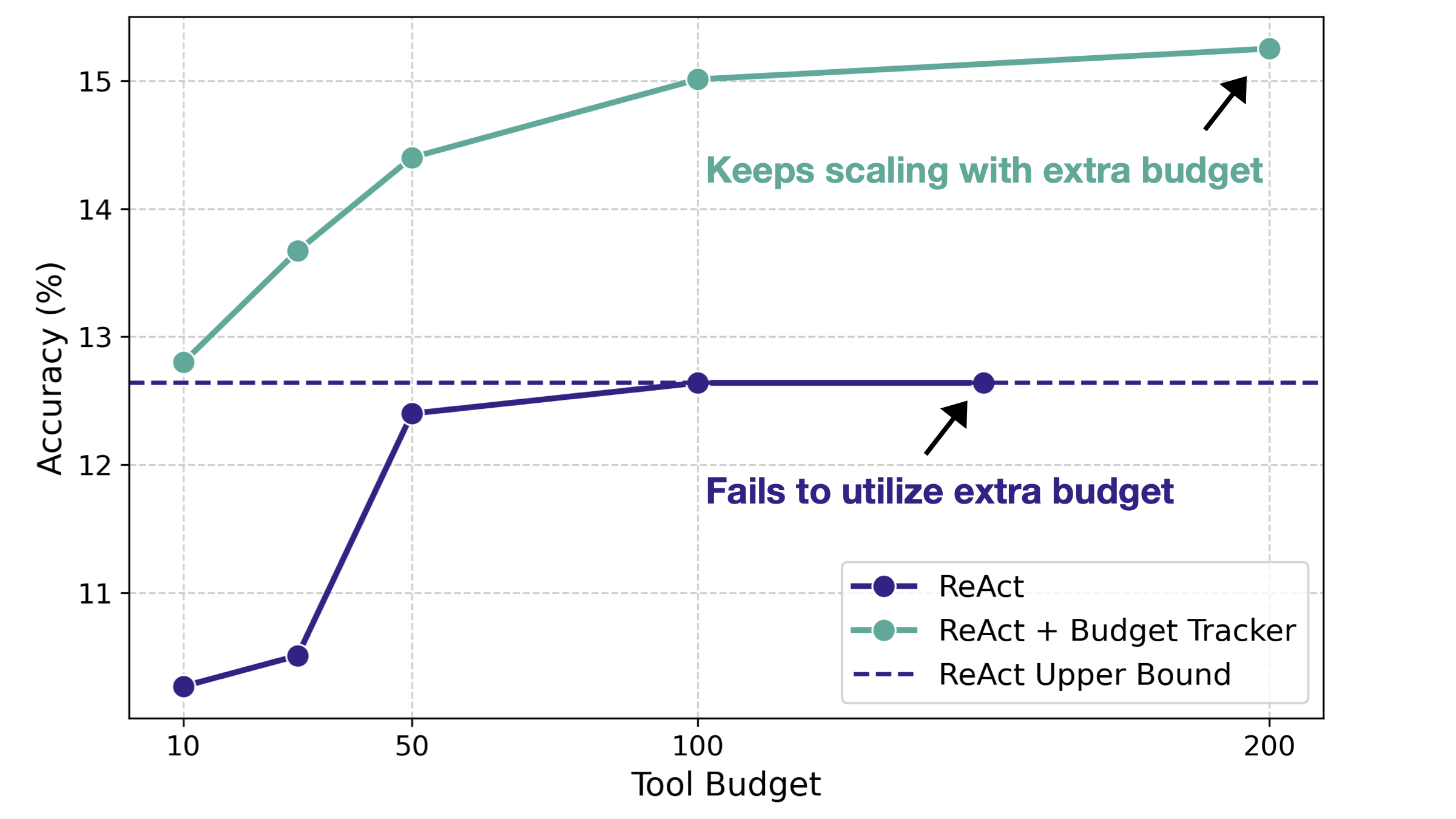

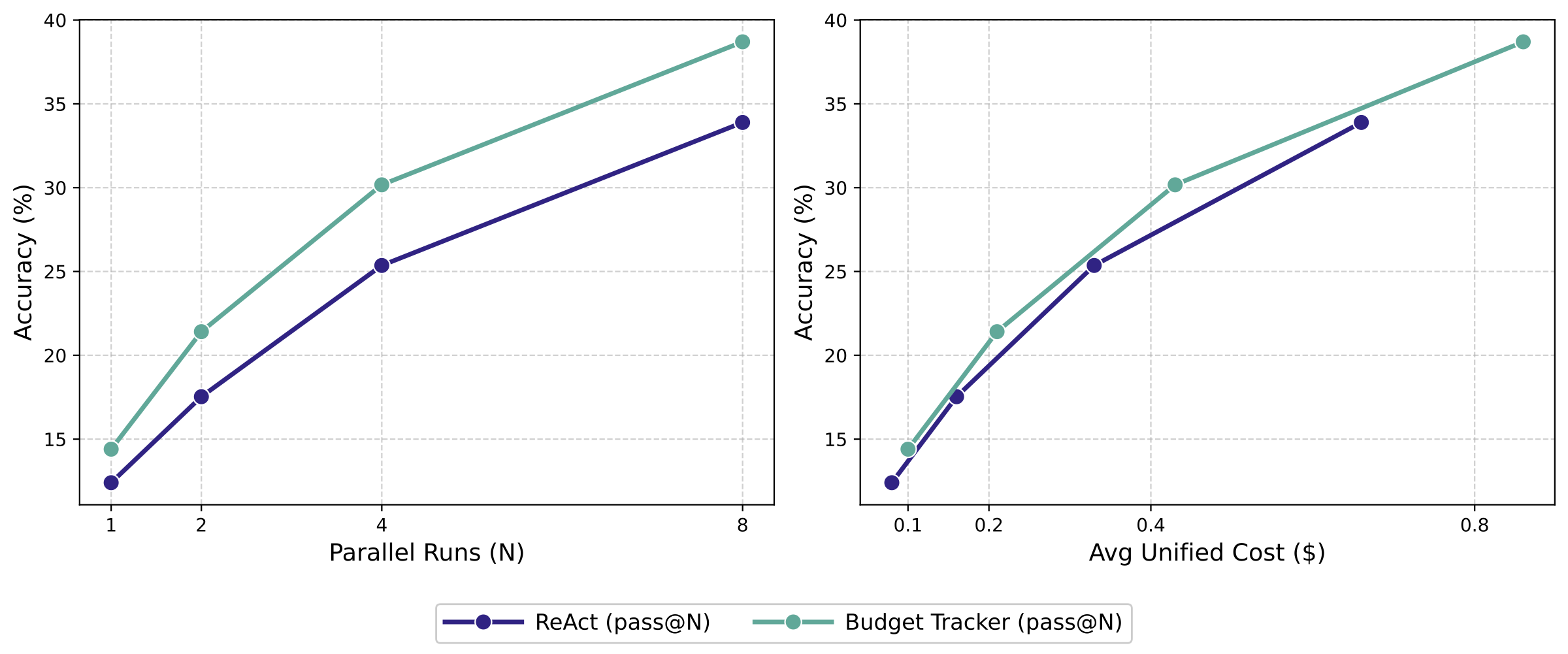

仅通过加入预算感知,Budget Tracker 就能促进持续扩展。图 3 展示了 Gemini-2.5-Pro 在 BrowseComp 上随工具预算增加的表现。缺乏预算感知时,标准 ReAct 基线在预算为 100 时即饱和;此后即使上下文窗口并未填满,它也无法利用额外分配预算。这种天花板源于推理过程过早终止:智能体要么认为已找到足够答案,要么认为卡住并放弃,却意识不到仍有可用资源。Budget Tracker 则显式告知剩余资源,使模型能够利用更大预算并继续扩展性能。

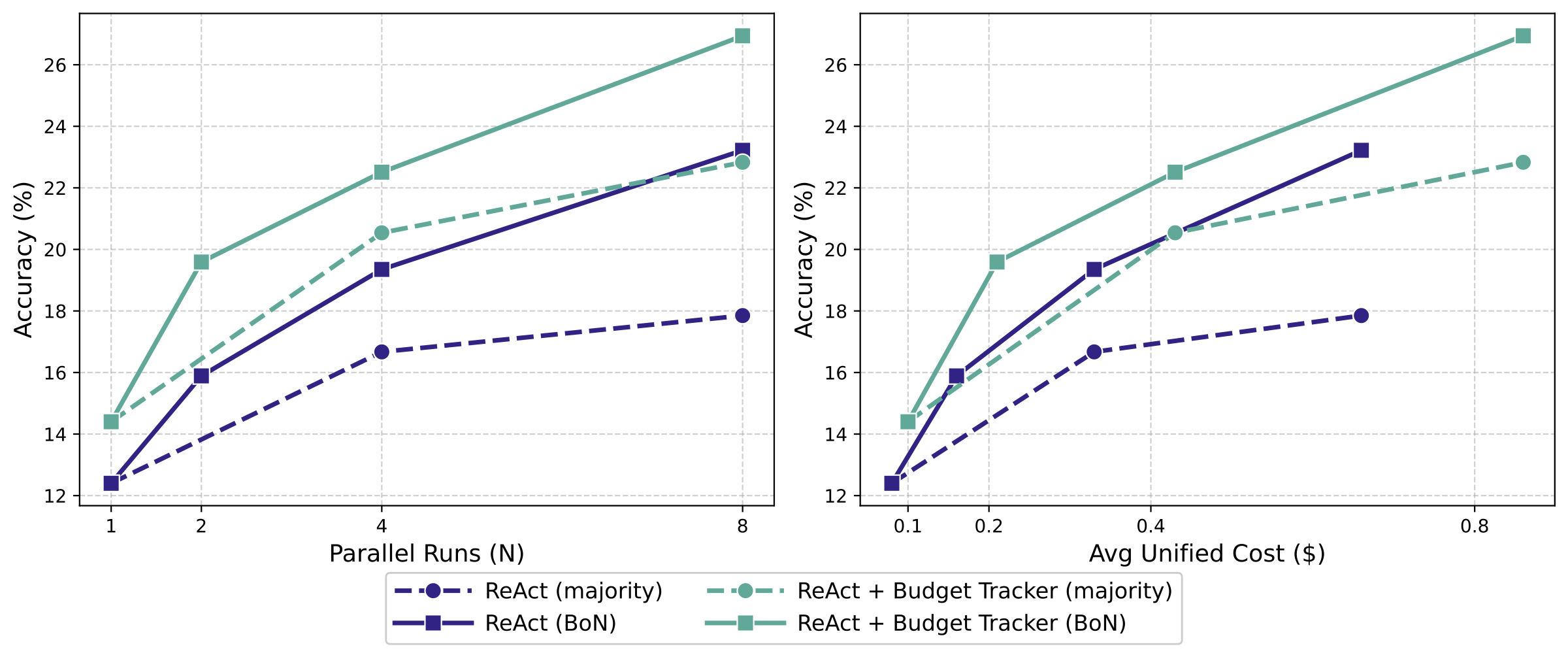

3.4 扩展策略分析

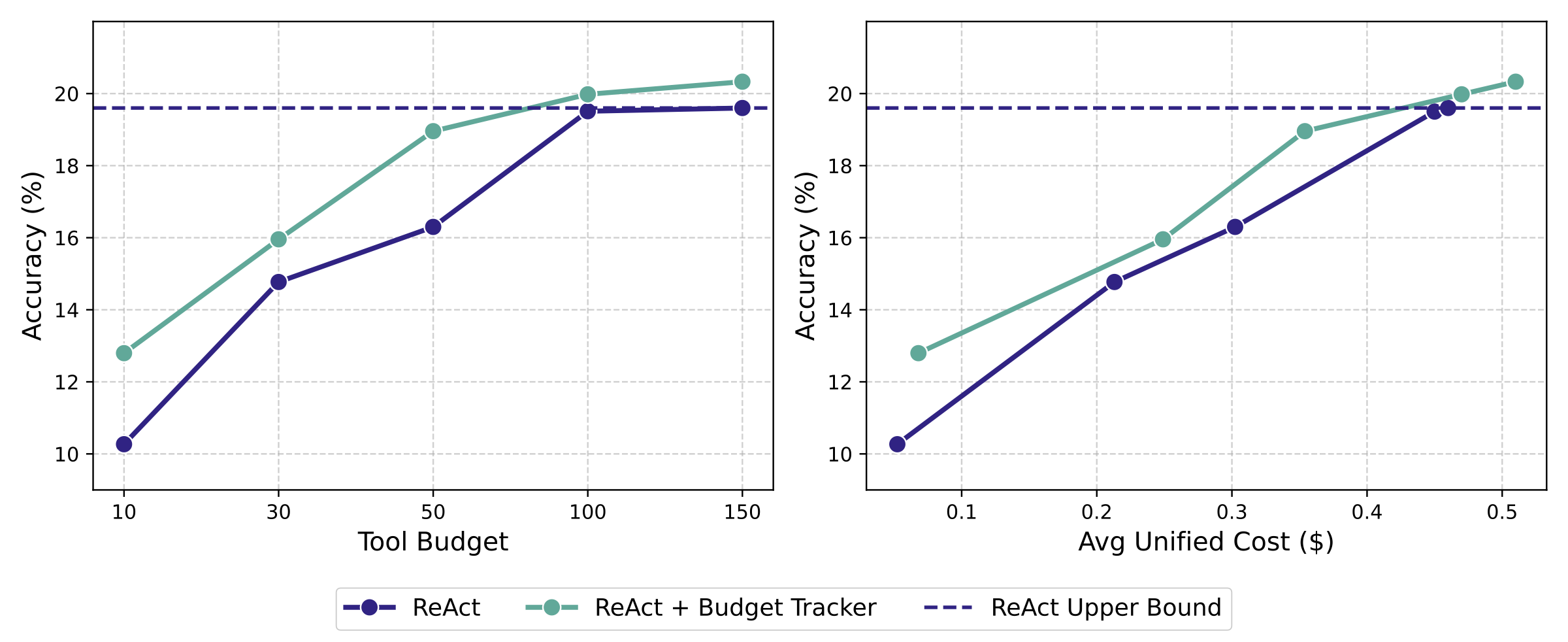

在不同测试时扩展策略下,Budget Tracker 都能稳定推进帕累托前沿并展现鲁棒有效性。顺序扩展通过提示智能体继续推理、探索更多信息来源来促使其发起更多工具调用;当智能体连续五次拒绝调用工具时停止提示。图 4 表明:该策略确实能让 ReAct 进一步提升准确率,但最终仍会触及性能天花板——智能体会自信地认为无需更多工具调用。相比之下,Budget Tracker 取得更优且更持续的扩展曲线,并能在 ReAct 平台期后继续带来性能增益,同时推进成本–性能曲线的帕累托前沿。

在并行扩展中,我们对 Gemini-2.5-Pro 将单次运行预算固定为 50,因为经验观察表明 BrowseComp 中仅有 0.8% 的样本需要超过该上限(见附录 B.1)。图 5 使用相同采样规模,报告 Majority Vote 与 Best-of-N(Pass@N 见附录 B.2);右侧子图展示了对应的成本–性能趋势,其中 Budget Tracker 始终给出更优曲线。

4. BATS:预算感知的智能体测试时扩展框架

在预算感知已被证明有效的基础上,我们进一步探究它如何增强智能体编排,并影响规划与自验证等关键行为。我们提出 BATS:一个在显式预算约束下对工具增强智能体进行测试时扩展的框架。如图 6 所示,给定信息查询问题与工具调用预算,BATS 先通过内部推理形成结构化行动计划并决定调用哪些工具。工具调用由特定 token 触发,工具返回结果被追加到推理序列中,从而以新证据扩展上下文。

当智能体提出候选答案后,验证模块检查其有效性,并决定是继续当前序列还是在剩余预算下发起新的尝试。迭代过程在任一预算资源耗尽时终止。最后,使用“LLM 作为裁判”在所有通过验证的答案中选择最佳答案。BATS 的完整系统提示词见附录 C。

BATS 的核心设计原则是预算感知:在整个执行过程中,Budget Tracker 在每轮迭代更新资源使用与剩余预算。这种持续的预算信号会影响规划、工具使用与验证行为,使智能体能在受限资源下自适应且高效地分配预算。下面分别介绍 BATS 各模块如何纳入预算感知。

4.1 预算感知规划

BATS 的规划同时包含约束分解与结构化动态规划。选择合适的起点至关重要:好的入口能缩小搜索空间、节省预算;而糟糕的选择会迅速耗尽预算(示例见附录 D.1)。为此,我们提示智能体先进行约束分解,将问题隐含线索分为两类:(1) 探索(exploration)线索:用于扩展候选空间;(2) 验证(verification)线索:用于验证特定属性。验证线索有时能直接“捷径”指向答案,但过早依赖它风险较大,因为它可能消耗资源却不保证带来进展。

我们进一步要求智能体在执行中生成并维护一个显式计划。该树状计划充当动态清单:记录步骤状态、资源使用与分配,并引导后续行动。计划从不被覆盖:已完成、失败或部分完成的步骤都会保留,以避免重复工具调用并保持完整执行轨迹(规划模块完整提示词见附录 C.2)。如图 6 的规划块所示,计划中的单个步骤表示一个可能需要多次工具调用才能完成的子任务(例如获取候选列表)。

每轮迭代后,新信息可能引入新的分支、解决挂起步骤或否定低效路径。规划模块会依据当前剩余预算,动态调整探索广度与验证深度。

将约束分解、持久化结构化规划与持续的预算条件更新结合起来,使 BATS 能在可控、可解释的搜索过程中高效分配工具调用预算,在探索与验证子任务之间进行合理取舍。

4.2 预算感知自验证

当智能体提出答案后,自验证模块会重新评估当前推理轨迹及其资源使用情况(完整验证提示词见附录 C.3)。该过程首先进行逐约束的回溯检查:利用先前提取的探索与验证线索,评估每条约束是否已被满足、被反驳或仍不可验证。此细粒度检查能将候选答案直接与问题需求对齐。

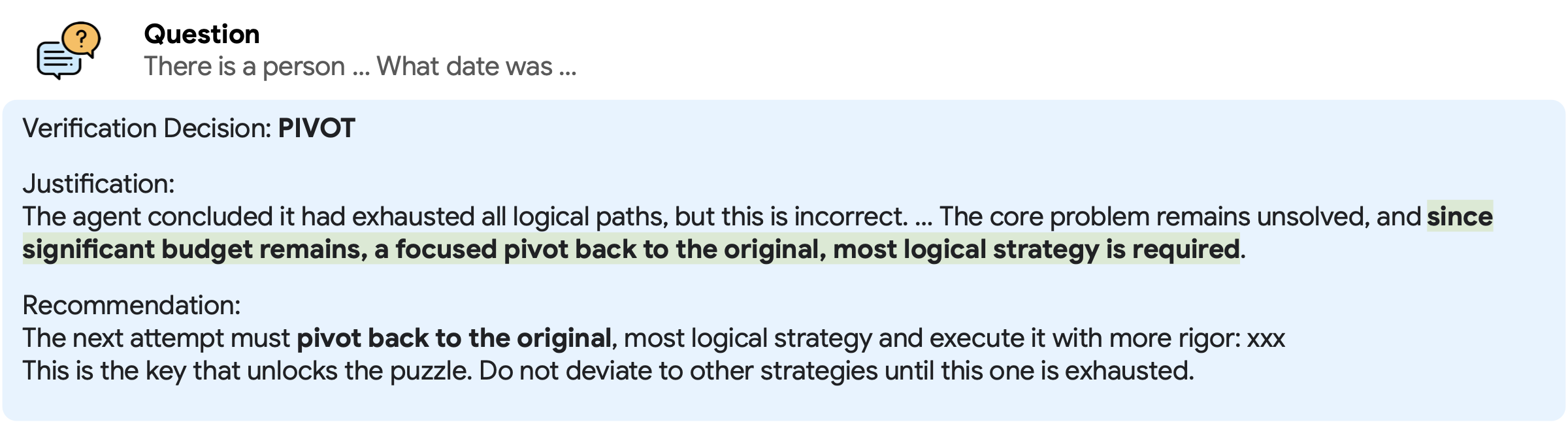

随后模块基于上述评估与预算状态做出验证决策:若所有约束均满足,则标记为 SUCCESS;若少数约束不可验证但轨迹仍有希望,且预算足以继续深挖,则选择 CONTINUE;若发现矛盾,或剩余预算不足以支持进一步调查,则应尽早终止昂贵或低收益方向并 PIVOT 到不同方向,以避免在仍有资源时把预算浪费在当前线索上。

当决策为 CONTINUE 或 PIVOT 时,模块还会生成一段简洁摘要,用以替换上下文中的原始轨迹:包括关键推理步骤、中间发现、失败原因与避免重复探索的优化建议。通过将轨迹压缩为紧凑而信息充分的摘要,验证器既能控制上下文长度,又能确保后续尝试仍以已获取信息为依据。

综合结构化约束检查、显式决策规则与预算感知的轨迹摘要,BATS 能更早终止无用轨迹、更高效地延续有希望的轨迹,并在严格预算约束下保持可靠进展。

5. 实验

5.1 设置

数据集。为评估 Web 搜索智能体,我们使用三个具有挑战性的信息查询基准:BrowseComp[20](1,266 个需要持续检索的困难网页浏览问题)、BrowseComp-ZH[21](289 个面向区域化 Web 环境的中文问题)、HLE-Search[23](从 Human’s Last Exam[22] 中筛选的 200 个明确需要搜索而非纯推理的子集)。

基线。我们将 BATS 与一系列模型与智能体框架对比:既包含通用基础模型[24,25,26,27,28],也包含针对智能体搜索任务进行专门微调的模型/框架[29,30,31,16]。为评估最终答案准确率,我们使用 Gemini-2.5-Flash 作为裁判模型,并采用文献 [22] 的评测提示词。HLE-Search 的基线结果从文献 [23] 抓取。

对于扩展方法,我们评估应用在 ReAct[19] 基线上的顺序扩展与并行扩展。

顺序扩展。为鼓励智能体在迭代执行中使用更多工具,我们参考文本推理中的做法[3]:每当智能体给出答案时追加提示,要求其重新思考并使用更多工具;该过程重复直到预算耗尽,随后提示其输出最终答案。

并行扩展。我们用温度采样生成多样推理路径。默认采用 Gemini-2.5-Flash 作为裁判,通过多数投票选择最常见答案[6](细节见附录 B.2)。在 BATS 的实验中,为对每个问题施加预算约束,我们会持续采样新序列直到预算完全消耗,因此不同问题的采样序列数量可能不同。

5.2 实现细节

我们在框架中使用 Gemini-2.5-Flash、Gemini-2.5-Pro[26] 与 Claude-Sonnet-4[28] 作为底座模型。默认情况下,我们通过设置 thinking budget 来禁用“思考模式”:对 Gemini-2.5-Flash 设为 0,对 Gemini-2.5-Pro 设为 1024。生成的最大新 token 数设置为:Gemini 65,536,Claude 64,000。智能体执行时温度设为 0.7 以鼓励探索;最终答案选择与答案评估使用确定性的温度 0.0。

Search 工具使用 Google Custom Search JSON API(https://developers.google.com/custom-search/v1/overview)。Browse 工具使用 Jina.ai(https://jina.ai/)与 Crawl4AI[32]。

6. 结果

6.1 主要结果

表 3 对比了不同 Web 搜索智能体的表现。在 BrowseComp 的严格预算约束(每个工具 100 次调用)下,BATS 相比基线方法取得稳定更优结果:使用 Gemini-2.5-Pro 时,在 BrowseComp 上达到 24.6%,在 BrowseComp-ZH 上达到 46.0%,在 HLE-Search 上达到 27.0%。关键在于:许多对比智能体依赖大量任务特定训练来提升表现,而 BATS 完全无需训练。这凸显了预算感知设计的有效性:在资源受限场景中,通过最大化每一次工具调用的效率,即可在无需额外微调的情况下获得更强结果。

| 方法 | 是否训练 | BrowseComp | BrowseComp-ZH | HLE-Search |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Only | ||||

| GPT-4o | ✗ | 0.6 | 6.2 | - |

| Claude-3.7-Sonnet | ✗ | 2.3 | 11.8 | - |

| Gemini-2.5-Flash★ | ✗ | 2.7 | 23.9 | 2.8 |

| Gemini-2.5-Pro★ | ✗ | 6.3 | 27.8 | 8.6 |

| OpenAI o1 | ✗ | 9.9 | 29.1 | - |

| Training-based Agents | ||||

| ASearcher | ✓ | 5.2 | 15.6 | - |

| WebSailor | ✓ | 12.0 | 30.1 | - |

| DeepDive | ✓ | 14.8 | 25.6 | - |

| WebExplorer | ✓ | 15.7 | 32.0 | - |

| OpenAI Deep Research | ✓ | 51.5 | 42.9 | 29.1 |

| Budget-constrained | ||||

| Claude-Sonnet-4 · ReAct | ✗ | 12.2 | 29.1 | 20.5 |

| Claude-Sonnet-4 · BATS(本文) | ✗ | 19.1 | 41.5 | 29.0 |

| Gemini-2.5-Flash · ReAct | ✗ | 9.7 | 26.5 | 14.7 |

| Gemini-2.5-Flash · BATS(本文) | ✗ | 14.3 | 34.3 | 19.5 |

| Gemini-2.5-Pro · ReAct | ✗ | 12.6 | 31.5 | 20.5 |

| Gemini-2.5-Pro · BATS(本文) | ✗ | 24.6 | 46.0 | 27.0 |

表 3:Web 搜索智能体的性能对比。带 ★ 的结果来自本文实验,其余基线分数引用自对应论文;“是否训练”表示是否针对 Web 搜索智能体任务做过专门训练。在本文预算设定中,每个工具的预算均为 100 次调用。

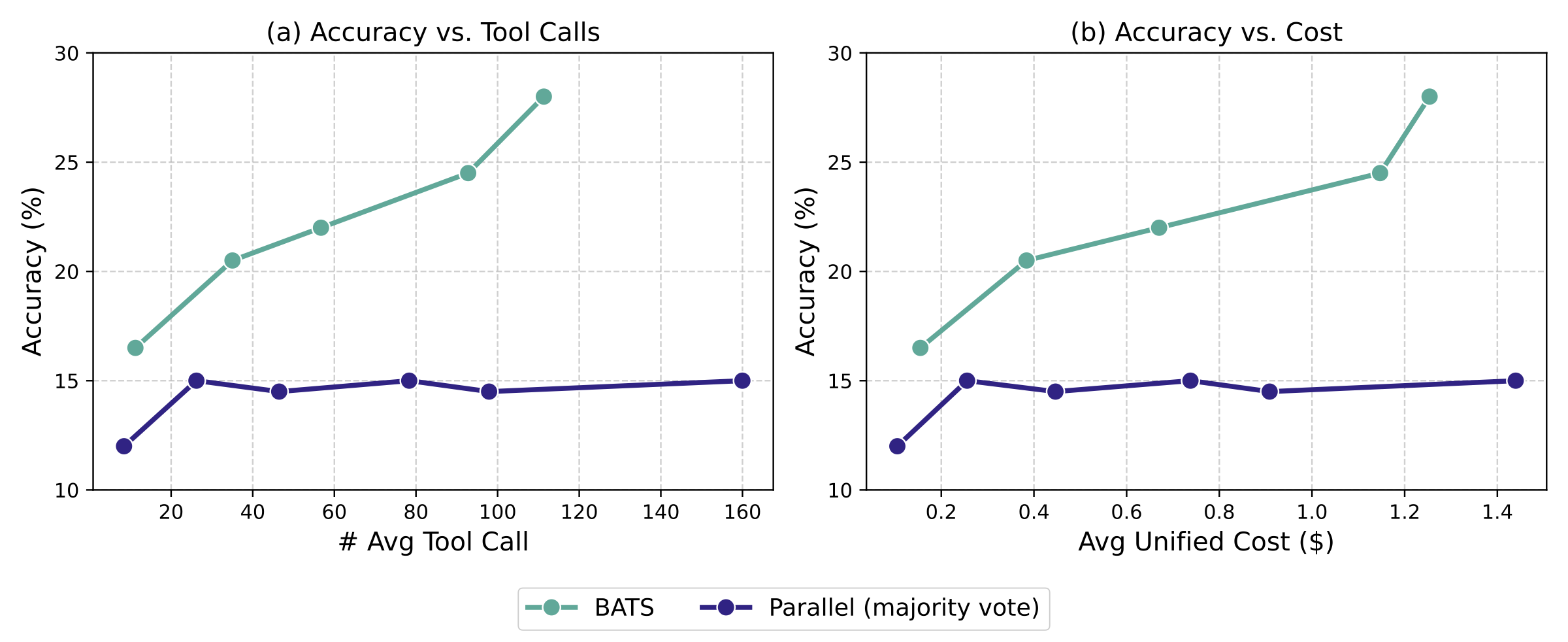

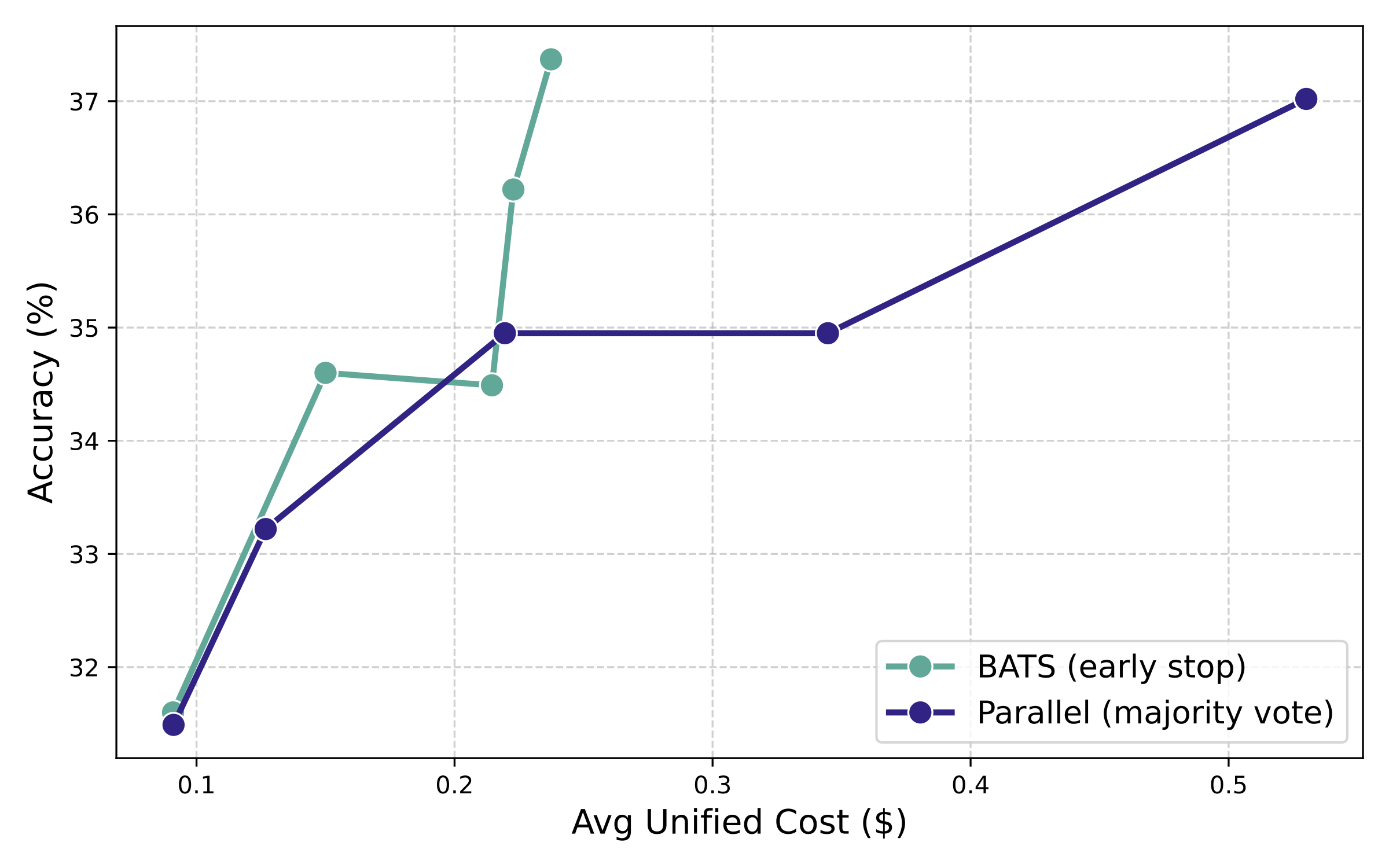

在相同预算约束下,BATS 取得更高性能。为更细致地理解扩展行为,我们在 BrowseComp 的随机 200 个样本子集上改变工具调用预算并评估性能。图 7(左)展示准确率随平均工具调用次数(search + browse)的变化;在所有预算水平下,BATS 始终优于并行多数投票基线,表明预算感知自适应能更有效地利用有限工具调用。

在统一成本意义下,BATS 仍取得更优扩展曲线。除工具调用次数外,我们还使用统一成本指标同时计入 token 与工具调用费用。图 7(右)显示:BATS 能在相近或更低成本下获得更高准确率,意味着它不仅在预算约束下更有效,也带来更好的成本–性能权衡。

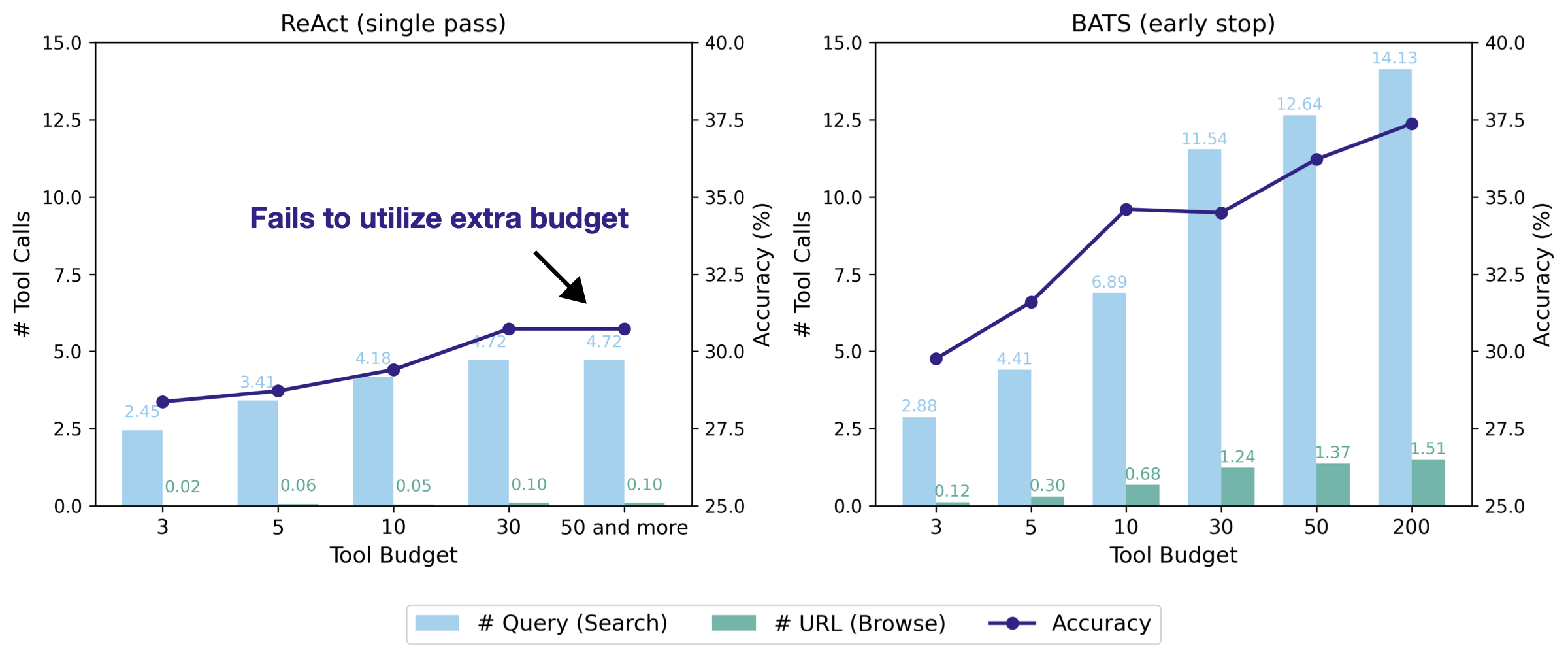

6.2 早停

我们分析在预算约束下允许智能体提前停止(无需耗尽所有工具调用)时,智能体解决问题的效率与效果。该设定更贴近真实场景:若智能体已足够自信,优先给出高效答案而非继续消耗资源。

为隔离该行为,我们仅关注智能体的第一次尝试:对 BATS,这指首次通过自验证的答案;对缺乏验证模块的基线,我们使用单次生成的输出作为其第一次尝试。若在该第一次尝试完成前任一工具预算耗尽,智能体会停止并基于已取得的进展输出最终答案。该评估同时考察效率与鲁棒性:智能体能否在不被迫用满预算的情况下快速解决问题。

预算感知使 BATS 能随资源增加而有效扩展。图 8 展示了使用 Gemini-2.5-Pro 在 BrowseComp-ZH 上的早停表现。横轴为预设的 search 与 browse 工具调用预算;柱状图为实际平均调用次数;折线为准确率。ReAct 基线(图 8 左)预算利用率很差:它几乎不使用 browse(平均少于 0.1 次),并很早进入平台期——当预算 ≥ 30 时准确率被限制在 30.7%。这反映了其缺乏预算感知、无法从额外资源中受益。

相比之下,BATS(图 8 右)表现出强预算自适应:预算越大,它越会策略性地增加 search 与 browse 使用,从而带来准确率的稳定提升(从 29.8%(budget=3)提升到 37.4%(budget=200))。值得注意的是,在预算仅为 5 时,BATS 已超过基线可达到的最佳准确率。这表明 BATS 能在相同或更少资源下做出更策略、更具成本效益的决策。更多分析见附录 B.4。

6.3 消融

| 方法 | BrowseComp | BrowseComp-ZH | HLE-Search |

|---|---|---|---|

| BATS | 18.7 | 39.1 | 23.0 |

| 去掉规划(w/o Planning) | 17.0 | 34.6 | 20.0 |

| 去掉验证(w/o Verification) | 15.4 | 37.7 | 22.0 |

| 去掉规划与验证(w/o Both) | 14.6 | 32.9 | 21.5 |

表 4:在 Gemini-2.5-Pro 上对 BATS 的消融结果:每个工具预算为 100。移除不同模块会在各数据集上造成不同程度的性能下降。

我们使用 Gemini-2.5-Pro 对 BATS 关键模块进行消融分析(表 4)。在所有设定与数据集上,智能体均分配每个工具 100 次调用预算。为更清晰呈现编排框架,我们聚焦早停机制下的 BATS:当答案被验证为成功即终止生成。

结果表明:移除规划模块会带来中等幅度性能下降;移除验证模块在 BrowseComp 上造成更显著下降(从 18.7% 降到 15.4%),说明验证模块对在解空间中导航并正确评估当前进度至关重要。移除两个模块后性能进一步降低(BrowseComp 上为 14.6%)。BrowseComp-ZH 与 HLE-Search 因数据集更小而存在一定方差;此外,HLE-Search 的问题通常更短且可验证细节更少,限制了验证模块的贡献。总体趋势确认:规划与验证模块都能正向提升编排框架的有效性。

8. 结论

本文给出了首个关于预算受限工具使用智能体及其测试时扩展行为的系统研究。我们发现:标准智能体由于缺乏资源感知往往会触及性能天花板。为解决这一问题,我们提出 Budget Tracker(提供持续预算信号的轻量插件)与 BATS(基于实时资源状态动态调整规划与验证的完整框架)。在多个模型与信息查询基准上的大量实验表明:预算感知能带来更强的智能体扩展能力,并稳定推进成本–性能帕累托前沿。通过将工具调用预算形式化为关键扩展维度,本文为构建高效、可自适应的工具增强智能体提供了更有原则的基础。

致谢

我们感谢 Rui Meng 以及 Google Cloud AI Research 的成员在论文准备过程中提供的宝贵反馈。

参考文献

- Y. Wu, Z. Sun, S. Li, S. Welleck, and Y. Yang. Inference scaling laws: An empirical analysis of compute-optimal inference for {LLM} problem-solving. In The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, {ICLR} 2025, Singapore, April 24-28, 2025. OpenReview.net, 2025b. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=VNckp7JEHn.

- C. Snell, J. Lee, K. Xu, and A. Kumar. Scaling {LLM} test-time compute optimally can be more effective than scaling model parameters. CoRR, abs/2408.03314, 2024. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2408.03314. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.03314.

- N. Muennighoff, Z. Yang, W. Shi, X. L. Li, L. Fei{-}Fei, H. Hajishirzi, L. Zettlemoyer, P. Liang, E. J. Cand{\`{e}}s, and T. Hashimoto. s1: Simple test-time scaling. CoRR, abs/2501.19393, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2501.19393. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.19393.

- J. Chen, J. Ren, X. Chen, C. Yang, R. Sun, and S. {\"{O}}. Arik. {SETS:} leveraging self-verification and self-correction for improved test-time scaling. CoRR, abs/2501.19306, 2025a. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2501.19306. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.19306.

- A. Madaan, N. Tandon, P. Gupta, S. Hallinan, L. Gao, S. Wiegreffe, U. Alon, N. Dziri, S. Prabhumoye, Y. Yang, S. Gupta, B. P. Majumder, K. Hermann, S. Welleck, A. Yazdanbakhsh, and P. Clark. Self-refine: Iterative refinement with self-feedback. In A. Oh, T. Naumann, A. Globerson, K. Saenko, M. Hardt, and S. Levine, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, NeurIPS 2023, New Orleans, LA, USA, December 10 - 16, 2023, 2023. URL http://papers.nips.cc/paper_files/paper/2023/hash/91edff07232fb1b55a505a9e9f6c0ff3-Abstract-Conference.html.

- X. Wang, J. Wei, D. Schuurmans, Q. V. Le, E. H. Chi, S. Narang, A. Chowdhery, and D. Zhou. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, {ICLR} 2023, Kigali, Rwanda, May 1-5, 2023. OpenReview.net, 2023. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=1PL1NIMMrw.

- B. C. A. Brown, J. Juravsky, R. Ehrlich, R. Clark, Q. V. Le, C. R{\'{e}}, and A. Mirhoseini. Large language monkeys: Scaling inference compute with repeated sampling. CoRR, abs/2407.21787, 2024. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2407.21787. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.21787.

- Q. Zhang, F. Lyu, Z. Sun, L. Wang, W. Zhang, Z. Guo, Y. Wang, I. King, X. Liu, and C. Ma. What, how, where, and how well? {A} survey on test-time scaling in large language models. CoRR, abs/2503.24235, 2025a. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2503.24235. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.24235.

- K. Zhu, H. Li, S. Wu, T. Xing, D. Ma, X. Tang, M. Liu, J. Yang, J. Liu, Y. E. Jiang, C. Zhang, C. Lin, J. Wang, G. Zhang, and W. Zhou. Scaling test-time compute for {LLM} agents. CoRR, abs/2506.12928, 2025b. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2506.12928. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.12928.

- F. Wang, H. Liu, Z. Dai, J. Zeng, Z. Zhang, Z. Wu, C. Luo, Z. Li, X. Tang, Q. He, and S. Wang. Agenttts: Large language model agent for test-time compute-optimal scaling strategy in complex tasks. CoRR, abs/2508.00890, 2025a. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2508.00890. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.00890.

- J. Shen, H. Bai, L. Zhang, Y. Zhou, A. Setlur, S. Tong, D. Caples, N. Jiang, T. Zhang, A. Talwalkar, and A. Kumar. Thinking vs. doing: Agents that reason by scaling test-time interaction. CoRR, abs/2506.07976, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2506.07976. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.07976.

- T. Han, Z. Wang, C. Fang, S. Zhao, S. Ma, and Z. Chen. Token-budget-aware {LLM} reasoning. In W. Che, J. Nabende, E. Shutova, and M. T. Pilehvar, editors, Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, {ACL} 2025, Vienna, Austria, July 27 - August 1, 2025, pages 24842--24855. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2025b. URL https://aclanthology.org/2025.findings-acl.1274/.

- X. Pu, M. Saxon, W. Hua, and W. Y. Wang. {THOUGHTTERMINATOR:} benchmarking, calibrating, and mitigating overthinking in reasoning models. CoRR, abs/2504.13367, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2504.13367. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.13367.

- Anthropic. Effective context engineering for ai agents, Sept. 2025c. URL https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/effective-context-engineering-for-ai-agents.

- M. Team, S. Bai, L. Bing, C. Chen, G. Chen, Y. Chen, Z. Chen, Z. Chen, J. Dai, X. Dong, W. Dou, Y. Deng, Y. Fu, J. Ge, C. Han, T. Huang, Z. Huang, J. Jiao, S. Jiang, T. Jiao, X. Jian, L. Lei, R. Li, R. Luo, T. Li, X. Lin, Z. Liu, Z. Li, J. Ni, Q. Ren, P. Sun, S. Su, C. Tao, B. Wang, H. Wang, H. Wang, J. Wang, J. Wang, J. Wang, L. Wang, S. Wang, W. Wang, Z. Wang, J. Xu, S. Xing, C. Yang, H. Ye, J. Yu, Y. Yu, M. Zhong, T. Zhao, X. Zhu, Y. Zhou, Y. Zhang, and Z. Zhu. Mirothinker: Pushing the performance boundaries of open-source research agents via model, context, and interactive scaling, 2025b. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.11793.

- R. Lu, Z. Hou, Z. Wang, H. Zhang, X. Liu, Y. Li, S. Feng, J. Tang, and Y. Dong. Deepdive: Advancing deep search agents with knowledge graphs and multi-turn rl, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.10446.

- Google. Gemini deep research — your personal research assistant. https://gemini.google/overview/deep-research/, 2025.

- OpenAI. Introducing deep research. https://openai.com/index/introducing-deep-research/, 2025.

- S. Yao, J. Zhao, D. Yu, N. Du, I. Shafran, K. R. Narasimhan, and Y. Cao. React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, {ICLR} 2023, Kigali, Rwanda, May 1-5, 2023. OpenReview.net, 2023. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=WE_vluYUL-X.

- J. Wei, Z. Sun, S. Papay, S. McKinney, J. Han, I. Fulford, H. W. Chung, A. T. Passos, W. Fedus, and A. Glaese. Browsecomp: {A} simple yet challenging benchmark for browsing agents. CoRR, abs/2504.12516, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2504.12516. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.12516.

- P. Zhou, B. Leon, X. Ying, C. Zhang, Y. Shao, Q. Ye, D. Chong, Z. Jin, C. Xie, M. Cao, Y. Gu, S. Hong, J. Ren, J. Chen, C. Liu, and Y. Hua. Browsecomp-zh: Benchmarking web browsing ability of large language models in chinese. CoRR, abs/2504.19314, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2504.19314. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.19314.

- L. Phan, A. Gatti, Z. Han, N. Li, J. Hu, H. Zhang, S. Shi, M. Choi, A. Agrawal, A. Chopra, A. Khoja, R. Kim, J. Hausenloy, O. Zhang, M. Mazeika, D. Anderson, T. Nguyen, M. Mahmood, F. Feng, S. Y. Feng, H. Zhao, M. Yu, V. Gangal, C. Zou, Z. Wang, J. P. Wang, P. Kumar, O. Pokutnyi, R. Gerbicz, S. Popov, J. Levin, M. Kazakov, J. Schmitt, G. Galgon, A. Sanchez, Y. Lee, W. Yeadon, S. Sauers, M. Roth, C. Agu, S. Riis, F. Giska, S. Utpala, Z. Giboney, G. M. Goshu, J. of Arc Xavier, S. Crowson, M. M. Naiya, N. Burns, L. Finke, Z. Cheng, H. Park, F. Fournier{-}Facio, J. Wydallis, M. Nandor, A. Singh, T. Gehrunger, J. Cai, B. McCarty, D. Duclosel, J. Nam, J. Zampese, R. G. Hoerr, A. Bacho, G. A. Loume, A. Galal, H. Cao, A. C. Garretson, D. Sileo, Q. Ren, D. Cojoc, P. Arkhipov, U. Qazi, L. Li, S. Motwani, C. S. de Witt, E. Taylor, J. Veith, E. Singer, T. D. Hartman, P. Rissone, J. Jin, J. W. L. Shi, C. G. Willcocks, J. Robinson, A. Mikov, A. Prabhu, L. Tang, X. Alapont, J. L. Uro, K. Zhou, E. de Oliveira Santos, A. P. Maksimov, E. Vendrow, K. Zenitani, J. Guillod, Y. Li, J. Vendrow, V. Kuchkin, and N. Ze{-}An. Humanity's last exam. CoRR, abs/2501.14249, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2501.14249. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.14249.

- R. Han, Y. Chen, Z. CuiZhu, L. Miculicich, G. Sun, Y. Bi, W. Wen, H. Wan, C. Wen, S. Ma{\^{\i}}tre, G. Lee, V. Tirumalashetty, E. Xue, Z. Zhang, S. Haykal, B. Gokturk, T. Pfister, and C. Lee. Deep researcher with test-time diffusion. CoRR, abs/2507.16075, 2025a. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2507.16075. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.16075.

- A. Hurst, A. Lerer, A. P. Goucher, A. Perelman, A. Ramesh, A. Clark, A. Ostrow, A. Welihinda, A. Hayes, A. Radford, A. Madry, A. Baker{-}Whitcomb, A. Beutel, A. Borzunov, A. Carney, A. Chow, A. Kirillov, A. Nichol, A. Paino, A. Renzin, A. T. Passos, A. Kirillov, A. Christakis, A. Conneau, A. Kamali, A. Jabri, A. Moyer, A. Tam, A. Crookes, A. Tootoonchian, A. Kumar, A. Vallone, A. Karpathy, A. Braunstein, A. Cann, A. Codispoti, A. Galu, A. Kondrich, A. Tulloch, A. Mishchenko, A. Baek, A. Jiang, A. Pelisse, A. Woodford, A. Gosalia, A. Dhar, A. Pantuliano, A. Nayak, A. Oliver, B. Zoph, B. Ghorbani, B. Leimberger, B. Rossen, B. Sokolowsky, B. Wang, B. Zweig, B. Hoover, B. Samic, B. McGrew, B. Spero, B. Giertler, B. Cheng, B. Lightcap, B. Walkin, B. Quinn, B. Guarraci, B. Hsu, B. Kellogg, B. Eastman, C. Lugaresi, C. L. Wainwright, C. Bassin, C. Hudson, C. Chu, C. Nelson, C. Li, C. J. Shern, C. Conger, C. Barette, C. Voss, C. Ding, C. Lu, C. Zhang, C. Beaumont, C. Hallacy, C. Koch, C. Gibson, C. Kim, C. Choi, C. McLeavey, C. Hesse, C. Fischer, C. Winter, C. Czarnecki, C. Jarvis, C. Wei, C. Koumouzelis, and D. Sherburn. Gpt-4o system card. CoRR, abs/2410.21276, 2024. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2410.21276. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.21276.

- A. Jaech, A. Kalai, A. Lerer, A. Richardson, A. El{-}Kishky, A. Low, A. Helyar, A. Madry, A. Beutel, A. Carney, A. Iftimie, A. Karpenko, A. T. Passos, A. Neitz, A. Prokofiev, A. Wei, A. Tam, A. Bennett, A. Kumar, A. Saraiva, A. Vallone, A. Duberstein, A. Kondrich, A. Mishchenko, A. Applebaum, A. Jiang, A. Nair, B. Zoph, B. Ghorbani, B. Rossen, B. Sokolowsky, B. Barak, B. McGrew, B. Minaiev, B. Hao, B. Baker, B. Houghton, B. McKinzie, B. Eastman, C. Lugaresi, C. Bassin, C. Hudson, C. M. Li, C. de Bourcy, C. Voss, C. Shen, C. Zhang, C. Koch, C. Orsinger, C. Hesse, C. Fischer, C. Chan, D. Roberts, D. Kappler, D. Levy, D. Selsam, D. Dohan, D. Farhi, D. Mely, D. Robinson, D. Tsipras, D. Li, D. Oprica, E. Freeman, E. Zhang, E. Wong, E. Proehl, E. Cheung, E. Mitchell, E. Wallace, E. Ritter, E. Mays, F. Wang, F. P. Such, F. Raso, F. Leoni, F. Tsimpourlas, F. Song, F. von Lohmann, F. Sulit, G. Salmon, G. Parascandolo, G. Chabot, G. Zhao, G. Brockman, G. Leclerc, H. Salman, H. Bao, H. Sheng, H. Andrin, H. Bagherinezhad, H. Ren, H. Lightman, H. W. Chung, I. Kivlichan, I. O'Connell, I. Osband, I. C. Gilaberte, and I. Akkaya. Openai o1 system card. CoRR, abs/2412.16720, 2024. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2412.16720. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.16720.

- G. Comanici, E. Bieber, M. Schaekermann, I. Pasupat, N. Sachdeva, I. S. Dhillon, M. Blistein, O. Ram, D. Zhang, E. Rosen, L. Marris, S. Petulla, C. Gaffney, A. Aharoni, N. Lintz, T. C. Pais, H. Jacobsson, I. Szpektor, N. Jiang, K. Haridasan, A. Omran, N. Saunshi, D. Bahri, G. Mishra, E. Chu, T. Boyd, B. Hekman, A. Parisi, C. Zhang, K. Kawintiranon, T. Bedrax{-}Weiss, O. Wang, Y. Xu, O. Purkiss, U. Mendlovic, I. Deutel, N. Nguyen, A. Langley, F. Korn, L. Rossazza, A. Ram{\'{e}}, S. Waghmare, H. Miller, N. Byrd, A. Sheshan, R. H. S. Bhardwaj, P. Janus, T. Rissa, D. Horgan, S. Silver, A. Wahid, S. Brin, Y. Raimond, K. Kloboves, C. Wang, N. B. Gundavarapu, I. Shumailov, B. Wang, M. Pajarskas, J. Heyward, M. Nikoltchev, M. Kula, H. Zhou, Z. Garrett, S. Kafle, S. Arik, A. Goel, M. Yang, J. Park, K. Kojima, P. Mahmoudieh, K. Kavukcuoglu, G. Chen, D. Fritz, A. Bulyenov, S. Roy, D. Paparas, H. Shemtov, B. Chen, R. Strudel, D. Reitter, A. Roy, A. Vlasov, C. Ryu, C. Leichner, H. Yang, Z. Mariet, D. Vnukov, T. Sohn, A. Stuart, W. Liang, M. Chen, P. Rawlani, C. Koh, J. Co{-}Reyes, G. Lai, P. Banzal, D. Vytiniotis, J. Mei, and M. Cai. Gemini 2.5: Pushing the frontier with advanced reasoning, multimodality, long context, and next generation agentic capabilities. CoRR, abs/2507.06261, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2507.06261. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.06261.

- Anthropic. Claude 3.7 sonnet system card. https://assets.anthropic.com/m/785e231869ea8b3b/original/claude-3-7-sonnet-system-card.pdf, 2025a.

- Anthropic. Claude 4 system card: Claude opus 4 & claude sonnet 4. https://www-cdn.anthropic.com/6d8a8055020700718b0c49369f60816ba2a7c285.pdf, 2025b.

- K. Li, Z. Zhang, H. Yin, L. Zhang, L. Ou, J. Wu, W. Yin, B. Li, Z. Tao, X. Wang, W. Shen, J. Zhang, D. Zhang, X. Wu, Y. Jiang, M. Yan, P. Xie, F. Huang, and J. Zhou. Websailor: Navigating super-human reasoning for web agent. CoRR, abs/2507.02592, 2025b. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2507.02592. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.02592.

- J. Liu, Y. Li, C. Zhang, J. Li, A. Chen, K. Ji, W. Cheng, Z. Wu, C. Du, Q. Xu, J. Song, Z. Zhu, W. Chen, P. Zhao, and J. He. Webexplorer: Explore and evolve for training long-horizon web agents. 2025a. URL https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:281204359.

- J. Gao, W. Fu, M. Xie, S. Xu, C. He, Z. Mei, B. Zhu, and Y. Wu. Beyond ten turns: Unlocking long-horizon agentic search with large-scale asynchronous {RL}. CoRR, abs/2508.07976, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2508.07976. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.07976.

- UncleCode. Crawl4ai: Open-source llm friendly web crawler & scraper. https://github.com/unclecode/crawl4ai, 2024.

- Y. Zhang, J. Yang, Y. Yuan, and A. C. Yao. Cumulative reasoning with large language models. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res., 2025, 2025b. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=grW15p4eq2.

- L. Liu, Z. Wang, L. Li, C. Xu, Y. Lu, H. Liu, A. Sil, and M. Li. A simple "try again" can elicit multi-turn {LLM} reasoning. CoRR, abs/2507.14295, 2025b. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2507.14295. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.14295.

- J. Chen, Z. Xun, B. Zhou, H. Qi, Q. Zhang, Y. Chen, W. Hu, Y. Qu, W. Ouyang, and S. Hu. Do we truly need so many samples? multi-llm repeated sampling efficiently scales test-time compute. CoRR, abs/2504.00762, 2025b. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2504.00762. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.00762.

- G. Wan, Y. Wu, J. Chen, and S. Li. Reasoning aware self-consistency: Leveraging reasoning paths for efficient {LLM} sampling. In L. Chiruzzo, A. Ritter, and L. Wang, editors, Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, {NAACL} 2025 - Volume 1: Long Papers, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA, April 29 - May 4, 2025, pages 3613--3635. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2025. doi: 10.18653/V1/2025.NAACL-LONG.184. URL https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2025.naacl-long.184.

- Y. Li, P. Yuan, S. Feng, B. Pan, X. Wang, B. Sun, H. Wang, and K. Li. Escape sky-high cost: Early-stopping self-consistency for multi-step reasoning. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, {ICLR} 2024, Vienna, Austria, May 7-11, 2024. OpenReview.net, 2024. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=ndR8Ytrzhh.

- S. Nayab, G. Rossolini, G. C. Buttazzo, N. Manes, and F. Giacomelli. Concise thoughts: Impact of output length on {LLM} reasoning and cost. CoRR, abs/2407.19825, 2024. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2407.19825. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.19825.

- S. Welleck, A. Bertsch, M. Finlayson, H. Schoelkopf, A. Xie, G. Neubig, I. Kulikov, and Z. Harchaoui. From decoding to meta-generation: Inference-time algorithms for large language models. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res., 2024, 2024. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=eskQMcIbMS.

- M. Damani, I. Shenfeld, A. Peng, A. Bobu, and J. Andreas. Learning how hard to think: Input-adaptive allocation of {LM} computation. In The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, {ICLR} 2025, Singapore, April 24-28, 2025. OpenReview.net, 2025. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=6qUUgw9bAZ.

- H. Yen, A. Paranjape, M. Xia, T. Venkatesh, J. Hessel, D. Chen, and Y. Zhang. Lost in the maze: Overcoming context limitations in long-horizon agentic search. CoRR, abs/2510.18939, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2510.18939. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2510.18939.

- Z. Chen, X. Ma, S. Zhuang, P. Nie, K. Zou, A. Liu, J. Green, K. Patel, R. Meng, M. Su, S. Sharifymoghaddam, Y. Li, H. Hong, X. Shi, X. Liu, N. Thakur, C. Zhang, L. Gao, W. Chen, and J. Lin. Browsecomp-plus: {A} more fair and transparent evaluation benchmark of deep-research agent. CoRR, abs/2508.06600, 2025c. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2508.06600. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.06600.

- R. Wong, J. Wang, J. Zhao, L. Chen, Y. Gao, L. Zhang, X. Zhou, Z. Wang, K. Xiang, G. Zhang, W. Huang, Y. Wang, and K. Wang. Widesearch: Benchmarking agentic broad info-seeking. CoRR, abs/2508.07999, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2508.07999. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.07999.

- K. Team, Y. Bai, Y. Bao, G. Chen, J. Chen, N. Chen, R. Chen, Y. Chen, Y. Chen, Y. Chen, et al. Kimi k2: Open agentic intelligence. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.20534, 2025a.

- B. Li, B. Zhang, D. Zhang, F. Huang, G. Li, G. Chen, H. Yin, J. Wu, J. Zhou, K. Li, L. Su, L. Ou, L. Zhang, P. Xie, R. Ye, W. Yin, X. Yu, X. Wang, X. Wu, X. Chen, Y. Zhao, Z. Zhang, Z. Tao, Z. Zhang, Z. Qiao, C. Wang, D. Yu, G. Fu, H. Shen, J. Yang, J. Lin, J. Zhang, K. Zeng, L. Yang, H. Yin, M. Song, M. Yan, P. Xia, Q. Xiao, R. Min, R. Ding, R. Fang, S. Chen, S. Huang, S. Wang, S. Cai, W. Shen, X. Wang, X. Guan, X. Geng, Y. Shi, Y. Wu, Z. Chen, Z. Li, and Y. Jiang. Tongyi deepresearch technical report. CoRR, abs/2510.24701, 2025a. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2510.24701. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2510.24701.

- B. Jin, H. Zeng, Z. Yue, D. Wang, H. Zamani, and J. Han. Search-r1: Training llms to reason and leverage search engines with reinforcement learning. CoRR, abs/2503.09516, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2503.09516. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.09516.

- J. Wu, B. Li, R. Fang, W. Yin, L. Zhang, Z. Tao, D. Zhang, Z. Xi, Y. Jiang, P. Xie, F. Huang, and J. Zhou. Webdancer: Towards autonomous information seeking agency. CoRR, abs/2505.22648, 2025a. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2505.22648. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.22648.

- Z. Tao, J. Wu, W. Yin, J. Zhang, B. Li, H. Shen, K. Li, L. Zhang, X. Wang, Y. Jiang, P. Xie, F. Huang, and J. Zhou. Webshaper: Agentically data synthesizing via information-seeking formalization. CoRR, abs/2507.15061, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2507.15061. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.15061.

- R. Ye, Z. Zhang, K. Li, H. Yin, Z. Tao, Y. Zhao, L. Su, L. Zhang, Z. Qiao, X. Wang, P. Xie, F. Huang, S. Chen, J. Zhou, and Y. Jiang. Agentfold: Long-horizon web agents with proactive context management. CoRR, abs/2510.24699, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2510.24699. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2510.24699.

- W. Li, J. Lin, Z. Jiang, J. Cao, X. Liu, J. Zhang, Z. Huang, Q. Chen, W. Sun, Q. Wang, H. Lu, T. Qin, C. Zhu, Y. Yao, S. Fan, X. Li, T. Wang, P. Liu, K. Zhu, H. Zhu, D. Shi, P. Wang, Y. Guan, X. Tang, M. Liu, Y. E. Jiang, J. Yang, J. Liu, G. Zhang, and W. Zhou. Chain-of-agents: End-to-end agent foundation models via multi-agent distillation and agentic {RL}. CoRR, abs/2508.13167, 2025c. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2508.13167. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.13167.

- X. Li, G. Dong, J. Jin, Y. Zhang, Y. Zhou, Y. Zhu, P. Zhang, and Z. Dou. Search-o1: Agentic search-enhanced large reasoning models. CoRR, abs/2501.05366, 2025d. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2501.05366. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.05366.

- H. Zhu, T. Qin, K. Zhu, H. Huang, Y. Guan, J. Xia, Y. Yao, H. Li, N. Wang, P. Liu, T. Peng, X. Gui, X. Li, Y. Liu, Y. E. Jiang, J. Wang, C. Zhang, X. Tang, G. Zhang, J. Yang, M. Liu, X. Gao, J. Liu, and W. Zhou. Oagents: An empirical study of building effective agents. CoRR, abs/2506.15741, 2025a. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2506.15741. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.15741.

- Z. Qiao, G. Chen, X. Chen, D. Yu, W. Yin, X. Wang, Z. Zhang, B. Li, H. Yin, K. Li, R. Min, M. Liao, Y. Jiang, P. Xie, F. Huang, and J. Zhou. Webresearcher: Unleashing unbounded reasoning capability in long-horizon agents. 2025. URL https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:281325175.

- T. Qin, Q. Chen, S. Wang, H. Xing, K. Zhu, H. Zhu, D. Shi, X. Liu, G. Zhang, J. Liu, Y. E. Jiang, X. Gao, and W. Zhou. Flash-searcher: Fast and effective web agents via dag-based parallel execution. CoRR, abs/2509.25301, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2509.25301. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2509.25301.

- X. Pang, S. Tang, R. Ye, Y. Du, Y. Du, and S. Chen. Browsemaster: Towards scalable web browsing via tool-augmented programmatic agent pair. CoRR, abs/2508.09129, 2025. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2508.09129. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.09129.

- N. Wang, X. Hu, P. Liu, H. Zhu, Y. Hou, H. Huang, S. Zhang, J. Yang, J. Liu, G. Zhang, C. Zhang, J. Wang, Y. E. Jiang, and W. Zhou. Efficient agents: Building effective agents while reducing cost. CoRR, abs/2508.02694, 2025b. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2508.02694. URL https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.02694.

注:参考文献按本文首次引用顺序编号,对应正文中的方括号引用。

附录

A. 实验细节

A.1 资源成本

工具调用成本由提供方定价决定。为标准化计费,我们将 search API 调用与网页浏览动作的单次调用统一定价为 $0.001。由于不同 URL 会产生不同长度的文本与 token 数,该按次费率是根据所有实验的后验统计计算得到的平均值。

Token 消耗则单独计费,遵循 API 提供方的官方定价模型(Vertex AI 定价:https://cloud.google.com/vertex-ai/generative-ai/pricing)。

A.2 实现细节

为控制上下文长度,我们采用若干简单的上下文管理策略。对每次 browse 调用,抓取的网页在发送给模型前会被截断为 150,000 个字符。每轮迭代中,我们丢弃更早步骤的工具输出,仅保留最近一次工具响应,避免上下文随累计工具结果而增长。

在 BATS 的验证模块中,我们进一步通过周期性摘要控制上下文规模。由于智能体决定何时触发验证模块,我们在每次验证调用时做检查:若自上次更新以来已超过 $K$ 轮迭代(实验中 $K=10$),则用来自验证输出的精简摘要替换更早的推理轨迹。

B. 额外分析

B.1 工具使用

| 模型 | 预算 | Acc % | Query(search) | URL(browse) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 平均次数 | Over-Budget % | 平均次数 | Over-Budget % | |||

| Gemini-2.5-Pro | 30 | 10.5 | 13.77 | 9.24 | 1.33 | 0.00 |

| 50 | 12.4 | 13.95 | 0.79 | 1.31 | 0.00 | |

| 100 | 12.6 | 14.24 | 0.00 | 1.36 | 0.00 | |

| Gemini-2.5-Flash | 30 | 9.0 | 22.77 | 42.81 | 1.04 | 0.00 |

| 50 | 9.7 | 28.88 | 14.22 | 1.24 | 0.00 | |

| 100 | 10.0 | 29.93 | 2.6 | 1.36 | 0.00 | |

表 B.1:BrowseComp 上 ReAct 基线的资源使用统计(Gemini-2.5-Pro 与 Gemini-2.5-Flash)。“Over-Budget %” 表示触及预算上限的样本比例。

表 B.1 展示了 ReAct 基线在 BrowseComp 上不同预算约束下的工具使用情况。随着可用预算增加,智能体能与环境进行更多交互,准确率也随之提高。“Over-Budget %” 表示耗尽预算的样本比例:对 Gemini-2.5-Pro,仅有 0.8% 的样本需要超过 50 次工具调用;而 Gemini-2.5-Flash 对工具依赖更高,有 2.6% 的查询在预算为 100 时仍会超出。值得注意的是,Flash 模型发出的 search 查询数量约为 Pro 的两倍,这表明 Gemini-2.5-Pro 更强的参数化知识能让其更高效地导航搜索空间,从而减少对外部证据的依赖,以更少工具调用解决问题。

B.2 并行扩展细节

对 Majority Vote,我们聚合不同采样的最终答案,并使用裁判模型(Gemini-2.5-Flash)识别共识答案。对 Best-of-N,我们将所有响应轨迹提供给裁判模型,并选择最有希望的一个。对 Pass@N,当采样的任一响应包含正确答案时计为 1。

上述评估使用的提示词见附录 C.4。图 B.1 进一步报告了并行扩展设定下 ReAct 与 Budget Tracker 的 Pass@N 结果:在不同预算与成本水平下,Budget Tracker 都能取得更高总体准确率。

B.3 资源使用

表 B.2 报告了在 BrowseComp 上、使用 Gemini-2.5-Pro 的 BATS 中工具调用与 token 消耗的细粒度拆分,并与变体 BATS-response 对比(该变体保留以往轮次的完整工具响应;相比之下,BATS 会移除这些历史响应以优化上下文长度)。表中 token 使用以三元组形式报告:输入 / 输出 / 缓存(单位:万 token);“Veri. tokens” 表示自验证模块的 token 使用。

结果表明:移除历史工具响应不会损害性能(准确率相近),但能显著降低计算开销——缓存 token 明显减少,统一成本也随之降低。

| 方法 | Acc (%) | # search | # browse | 总 token(输入/输出/缓存,万) | Veri. token(输入/输出/缓存,万) | 成本 ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BATS | 24.6 | 87.3 | 13.6 | 32.1 / 6.9 / 39.3 | 1.1 / 1.2 / 7.6 | 1.1 |

| BATS-response | 24.3 | 84.4 | 14.6 | 33.6 / 6.5 / 91.8 | 1.0 / 1.3 / 17.1 | 1.2 |

表 B.2:资源使用对比:在保持与全上下文基线(BATS-response)相近准确率的同时,BATS 显著降低缓存 token 使用与统一成本。

B.4 早停

BATS 通过早停进一步推进成本–性能帕累托前沿。为直接、透明地比较成本效率,图 B.2 展示了准确率随实际统一成本的变化。BATS 给出更陡峭的性能曲线:在更低成本下取得更高准确率。BATS 在约 $0.23 的成本下即可达到 37% 以上准确率,而并行多数投票基线需要超过两倍成本(超过 $0.50)才能达到相近结果。轻微波动来自 BrowseComp-ZH 数据集规模较小。

这种效率得益于预算感知的验证模块:当找到令人满意的答案时可以尽早终止,从而减少不必要的开销。

B.5 规划模块

为评估规划模块的影响,我们将 ReAct 基线与我们的设计结合:引入约束分析与动态结构化的清单计划。对 search 查询与 browse URL,工具调用预算上限均设为 200。如表 B.3 的 Gemini-2.5-Pro 结果所示,仅加入规划模块就能提升智能体组织探索并更有效利用工具的能力,从而带来 1.8% 的性能增益。

| 方法 | Acc % | 平均 Query 数 | 平均 URL 数 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ReAct | 11.0 | 7.75 | 0.35 |

| ReAct + planning | 12.8 | 13.81 | 0.82 |

表 B.3:规划模块的效果:在相同预算下,规划模块能鼓励更好的组织与工具使用,从而提高平均性能。

C. 提示词

我们用于 Web 搜索智能体的提示词基于文献 [46] 与 [29] 构建。

C.1 ReAct + Budget Tracker

You are an AI reasoner with Google Search and Browsing tools. Solve the question by iterating: think, tool_code, tool_response, answer.

## Tools

You have access to 2 tools: search and browse.

{

"name": "search",

"description": "Performs batched web searches: supply an array 'query'; the tool retrieves the top 10 results for each query in one call.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"query": {

"type": "array",

"items": {

"type": "string"

},

"description": "Array of query strings. Include multiple complementary search queries in a single call."

}

},

"required": [

"query"

]

}

},

{

"name": "browse",

"description": "Visit webpage(s) and return the summary of the content.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"url": {

"type": "array",

"items": {"type": "string"},

"description": "The URL(s) of the webpage(s) to visit. Can be a single URL or an array of URLs."

},

"goal": {

"type": "string",

"description": "The specific information goal for browsing webpage(s)."

}

},

"required": [

"url",

"goal"

]

}

}

You should start with one or more cycles of (thinking about which tool to use -> performing tool code -> waiting for tool response), and end with (thinking about the answer -> answer of the question). The thinking processes, tool codes, tool responses, and answer are enclosed within their tags. There could be multiple thinking processes, tool codes, tool call parameters and tool response parameters.

## Budget

You have two independent budgets:

- Query Budget (for search)

- URL Budget (for browse)

Each string in 'query' or 'url' consumes 1 unit respectively.

After each <tool_response>, a <budget> tag shows remaining units.

You must ADAPT your strategy dynamically to the current budget state.

### HIGH Budget (>=70% remaining)

- Search: 3-5 diverse queries in one batch.

- Browse: up to 2-3 high-value URLs.

- Goal: Broad exploration, build context fast.

### MEDIUM Budget (30%-70%)

- Search: 2-3 precise, refined queries per cycle.

- Browse: 1-2 URLs that close key knowledge gaps.

- Goal: Converge; eliminate uncertainty efficiently.

### LOW Budget (10%-30%)

- Search: 1 tightly focused query.

- Browse: at most 1 most promising URL.

- Goal: Verify a single critical fact or finalize answer.

### CRITICAL (<10% remaining or 0 in one budget)

- Avoid using the depleted tool.

- Only perform 1 minimal-cost query or browse if absolutely essential.

- If uncertainty remains and no tool use is possible, output <answer>None</answer>.

## Step syntax

<think>

Thinking process. Analyze the query, your internal knowledge, and search results to build your reasoning. Always justify tool choices based on the remaining budgets.

</think>

<tool_code>

{"name": "tool name here", "arguments": {"parameter name here": parameter value here, "another parameter name here": another parameter value here, ...}}

</tool_code>

<tool_response>

tool_response here

</tool_response>

<budget>

Query Budget Used: [number], Query Budget Remaining: [number], URL Budget Used: [number], URL Budget Remaining: [number]

</budget>

Repeat <think><tool_code> until you have the final answer.

<answer> Final solution only. </answer>

## About answers

* Only write the final answer inside <answer> and </answer>.

* If you cannot find the answer, write <answer>None</answer>.C.2 规划模块(Budget-aware Planning Module in BATS)

## About questions

Questions contain two types of constraints: exploration and verification.

* Exploration: Broad, core requirements (e.g., birthday, profession). Use these for initial searches to surface candidates. You may combine 1-2 to form stronger queries.

* Verification: Narrow, specific details. Apply these only after you have candidates, to confirm or filter them. Never begin with verification constraints.

Start with exploration queries, then use verification to validate the results.

## About planning

Maintain a tree-structured checklist of actionable steps (each may require several tool calls).

- Mark each step with its status: [ ] pending, [x] done, [!] failed, [~] partial.

- Use numbered branches (1.1, 1.2) to represent alternative paths or candidate leads.

- Log resource usage after execution: (Query=#, URL=#).

- Keep all executed steps, never delete them, retain history to avoid repeats.

- Update dynamically as you reason and gather info, adding or revising steps as needed.

- Always consider current and remaining budget when updating the plan.C.3 自验证模块(Budget-aware Self-verification Module in BATS)

You are an AI Strategic Verifier. Your primary goal is to evaluate a proposed answer, assess the viability of the current problem-solving plan, and decide the best course of action: declare success, continue with the current plan, or pivot to a new one.

### Given Inputs

* Question: The original user question. An answer is believed to exist.

* Trajectory: The sequence of reasoning steps and tool calls taken so far in the current attempt.

* Current Answer: The final answer produced by the current attempt.

* Budget Status: Information on current tool call budget utilization and remaining budget, including search queries and browsing urls.

### Your Task: A 3-Step Process

You must proceed in the following order:

#### Step 1: Conduct Verification Analysis

First, perform a strict verification of the `Current Answer`.

* Go through each constraint from the original Question one by one.

* For each constraint, compare it against the `Current Answer` and the `Trajectory`.

* State your finding for each constraint: satisfied, contradicted, or unverifiable.

#### Step 2: Make a Strategic Decision

Based on your verification and the budget, make one of three decisions.

1. SUCCESS: If the verification in Step 1 passed (all constraints are satisfied). The task is complete.

2. CONTINUE: If the verification failed because few constraints are unverifiable, but the overall plan is still sound and salvageable. This is the choice if **both** of these conditions are true:

* Promising Path: The `Trajectory` is generally sound, and the failure was due to a correctable error.

* Sufficient Budget: There is enough `Remaining Budget` to attempt a correction on this path.

3. PIVOT: If the verification failed, signal to abandon the current plan and switch to another one. You should pivot if any of these conditions are true:

* Dead End: The `Trajectory` reveals a fundamental flaw in the current plan's logic that cannot be easily fixed.

* Failed Tool Calls: The Trajectory shows repeated, unsuccessful attempts to find certain info.

* Insufficient Budget: The `Remaining Budget` is too low to make another meaningful attempt or correction within the *current* plan.

#### Step 3: Summarize for the Next Step

This is the most critical step for guiding future actions.

You need to first provide a **trajectory summary**: Summarize the agent's reasoning trajectory into a concise narrative. Explain its initial goal, the logical steps taken, key findings and the final conclusion, emphasizing how key findings or contradictions caused the agent to change its strategy.

Then, provide additional details tailored to your decision in Step 2.

* If the decision is SUCCESS:

* No further detail needed.

* If the decision is CONTINUE / PIVOT:

* Failure Analysis: Diagnose the root cause of the failure. Identify the critical flaw (e.g., poor query design, flawed logic, misinterpreted evidence) and name the general failure pattern to prevent its recurrence.

* Useful information: Any useful intermediate findings or results from the current `Trajectory` that could be valuable inputs for the next attempt. This prevents redundant work.

* Strategic Recommendations: Provide actionable advice for the agent's next attempt. Suggest strategic pivots, new angles of investigation, or different ways to combine the problem's constraints. Explicitly state if it should backtrack to and resume from a specific step in the previous plan to avoid re-doing work.

### **Output Requirement**

Your final output must be a single JSON object with the following structure. Do not add any text before or after this JSON block.

```json

{

"verification": "Verification analysis",

"decision": "SUCCESS | CONTINUE | PIVOT",

"justification": "A concise explanation for your strategic decision. Why is it a success, a dead end, or a correctable error?",

"trajectory_summary": "The informative trajectory summary.",

"details": "A JSON object containing the additional details required by Step 3. For a SUCCESS decision, this can be an empty object {}."

}

```C.4 答案选择(Answer Selection)

Best-of-N Answer Selection

You are an expert evaluator. Your task is to select the most accurate and specific answer to an information-seeking question. The question has a deterministic answer. You'll be provided with several answers and their corresponding trajectories/verifications.

**Instructions:**

1. **Identify the Core Question:** Determine the exact piece of information the question is asking for (e.g., a person, a location, a date).

2. **Evaluate Candidates:** For each candidate phrase, assess its factual accuracy.

3. **Compare and Select:** Choose the answer that is more likely to be correct. You should never choose "None" as the answer.

**Output Format:**

First, provide a brief justification explaining why the chosen answer is the most accurate and specific choice. Then, on a new line, output the letter of the best option inside a box.

**Example:**

Justification: Answer B is the most specific correct location...

Answer: \\boxed{B}

---

Majority Vote Answer Selection

You are an expert evaluator. Your task is to select the answer that best represents the **majority vote** among the provided candidates. The question has a deterministic answer, and the goal is to identify which option most responses converge on. You'll be provided with several answers and their corresponding trajectories/verifications.

**Instructions:**

1. **Identify the Core Question:** Determine the exact piece of information the question is asking for (e.g., a person, a location, a date).

2. **Tally the Votes:** Review all candidate answers and count how many times each distinct answer (or near-equivalent variant) appears. Treat semantically equivalent responses as votes for the same candidate.

3. **Select the Majority:** Choose the answer that has the highest number of votes. If there is a tie, pick the option that is the most specific and consistent with the question. Never choose "None" or refuse to make a choice.

**Output Format:**

First, provide a brief justification explaining why the chosen answer was selected (e.g., ``Answer C has the majority of votes across candidates''). Then, on a new line, output the letter of the best option inside a box.

**Example:**

Justification: Answer B received the majority of votes and aligns most consistently with the question.

Answer: \\boxed{B}D. 案例研究

本节展示不同智能体的输出。为避免将案例内容“污染”到互联网中,我们移除了关键细节,仅展示智能体轨迹的片段。

D.1 自适应思考与规划

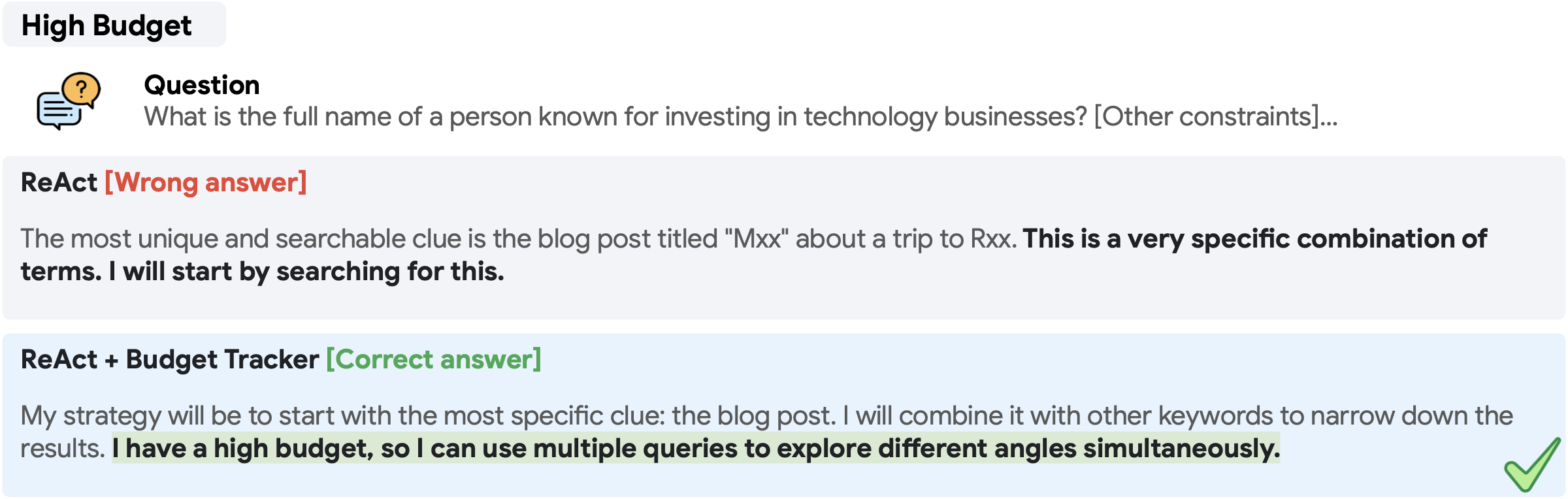

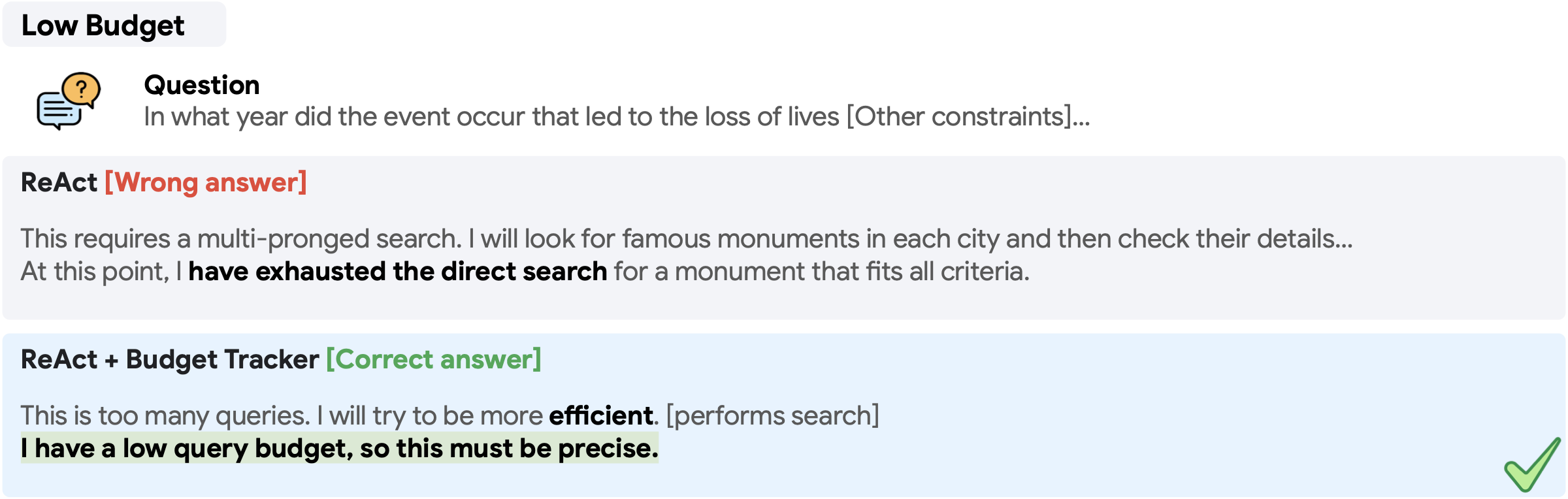

我们展示 Budget Tracker 如何通过预算感知,使智能体在高预算(图 D.1)或低预算(图 D.2)下采用不同策略。这些案例来自 Gemini-2.5-Pro 在 BrowseComp 上的轨迹。缺乏预算感知时,ReAct 往往采用蛮力式规划策略以穷举直接搜索,这会快速消耗所有资源并导致无法正确回答。

D.2 自适应验证

在图 D.3 中,我们展示自验证模块如何基于轨迹与资源状态做出预算感知的决策:它选择从当前尝试转向(pivot),因为剩余预算仍允许进一步调查。这些案例来自 Gemini-2.5-Pro 在 BrowseComp 上的轨迹。

E. 局限性

更多资源约束。本文给出了关于工具调用预算的首个实证分析,但更现实且更具挑战的场景是同时管理多种资源约束,例如 token 上限、推理延迟与工具调用预算。理解并控制智能体在多维约束下的行为,对在真实环境中部署可规模化系统十分重要。

资源分配。尽管我们观察到预算感知能带来更有效的扩展,但我们并未进一步探索智能体应如何在可用资源之间进行分配。我们的实证分析提示:模型常常低估自身实际资源消耗,这可能导致次优表现。发展更准确的资源估计与更有原则的预算分配策略,是一个很有前景的未来方向。

更智能的上下文管理。尽管我们采用了移除工具响应、摘要中间轨迹等简单上下文控制技术,但更高级的上下文工程仍较少被探索。设计更有效的“记忆”格式,并在上下文长度与性能之间找到合适平衡,是构建鲁棒且高效智能体的重要开放问题。